Civil Rights Icon Inspires MLK Day Marchers to ‘Have No Fear’

Undaunted by winter chill and slushy streets, a diverse and enthusiastic crowd of perhaps 100 marchers gathered in the cloudy early morning Saturday Jan. 18 at the Tinner Hill Monument to construct affirmative protest signs and march in celebration of the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the first day of the national Martin Luther King Day Holiday weekend.

The Tinner Hill Arch at 510 S. Washington St. was selected as the gathering place because the very first rural chapter of the NAACP was founded in Falls Church’s Tinner Hill neighborhood in 1918, as local Black civil rights activists protested overt racial segregation by the City of Falls Church.

This year’s MLK Day celebration was dubbed the Annual March for Unity and Freedom, with Social Justice Workshop and coordinated by the Social Justice Committee of Falls Church and Vicinity, the City of Falls Church, and the Chi Beta Omega Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.

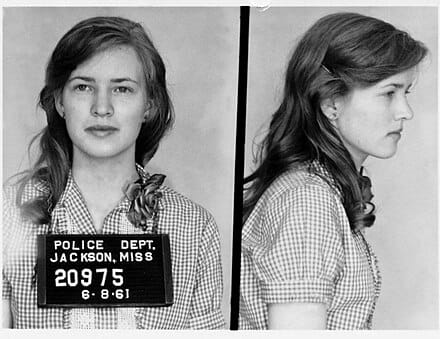

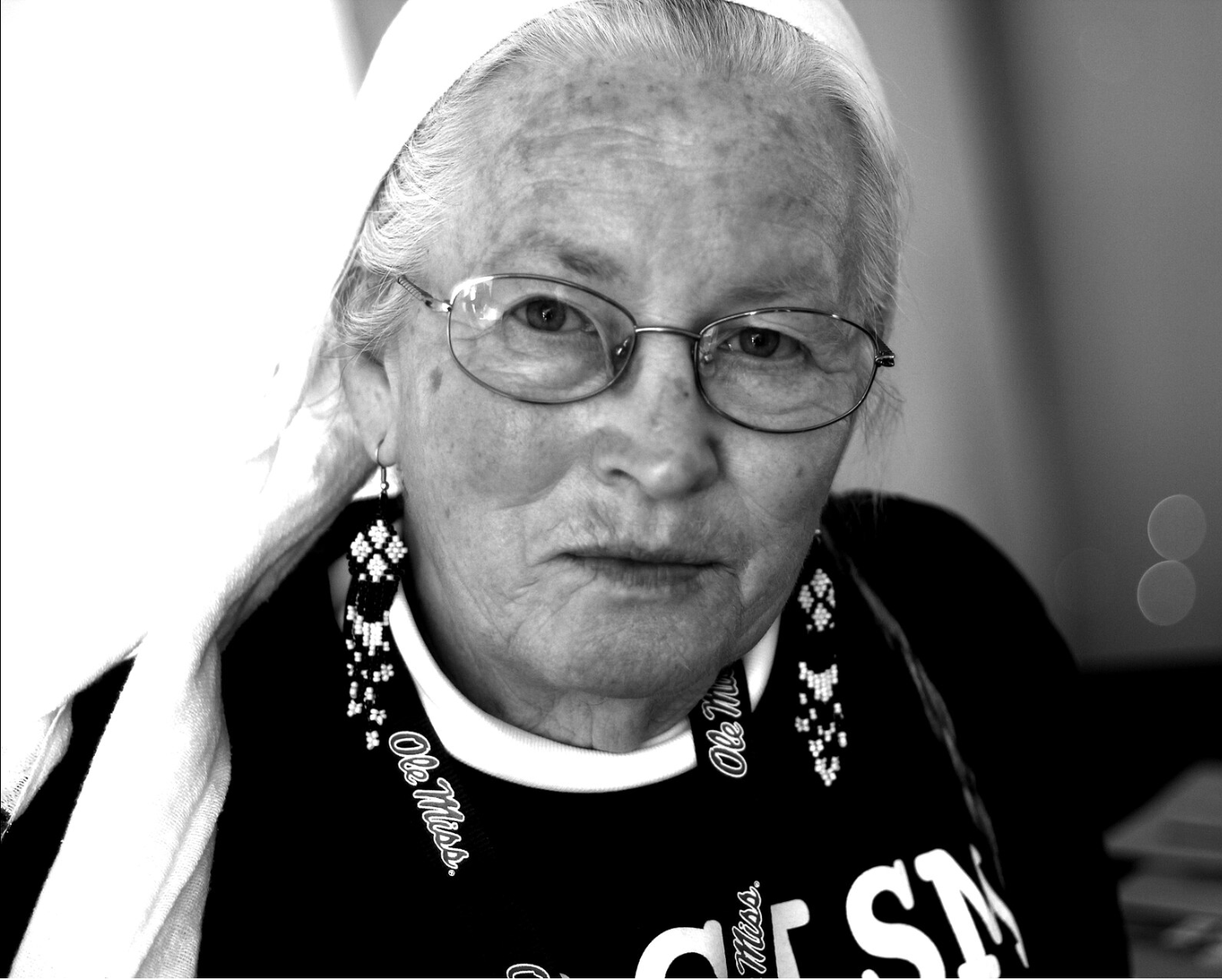

The day’s guest speaker, Civil Rights icon and activist Joan Mulholland, 83, was a major highlight of the day.

A Striking Organizational Success

In a striking organizational success, this year’s protest was allowed to march right down the middle of S. Washington St. (Lee Highway) in Falls Church with auto traffic closed, whereas last year, participants were confined to the sidewalks as cars and buses roared past.

Last year, MLK march organizers highlighted the slight: “Ironically, the march will take place along Lee Highway [S. Washington St.] where an African American community was taken by eminent domain to create a highway to honor the Commander of the Confederate Army, Gen. Robert E. Lee. We wish to honor the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., on the national holiday in his honor, but we won’t be allowed, by various government entities, to walk on the street honoring Robert E. Lee. In protest, we will march along this route, but will be required to walk along the sidewalk…”

So this year, the march took to the streets.

Following supportive and inspiring speeches by City of Falls Church Mayor Letty Hardi and Founder of the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation Ed Henderson – who mentioned the Lee Highway irony – and a prayer of invocation for the march, the well-bundled and joyous group processed east on S. Washington Street with signs aloft for nearly half a-mile to the Falls Church Episcopal. Along the march route, City of Falls Church Mayor Letty Hardi, City Council member Justine Underhill, and City Manager Wyatt Shields were spotted, and inside, former Council member Phil Duncan.

‘Mission Possible’: A Full Day’s Program

On arrival at the Falls Church Episcopal, the marchers were immediately treated to hot coffee, tea, beverages, and a full catered lunch. With spiritual music in the sanctuary, the afternoon program on the theme “Mission Possible – Protecting Freedom, Justice, and Democracy: What Can I Do?” began after lunch.

Following a welcome and invocation from retired pastor and guest Rev. Gregory Loewer, and a rousing, standing group-singalong of the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” by Social Justice Committee Music Coordinator Rich Scott, with vocals by Josephine Arrington and Shanel Thomas, it was time for the program’s Special Guest Speaker, Civil Rights icon and activist Joan Mulholland.

The Main Event: Guest Speaker, Joan Mulholland

While it may be difficult for younger people to imagine, protesting racially segregated facilities non-violently in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s – before the Civil Rights Acts of the mid-1960s – was not only extremely dangerous due to violent racist backlash, but was “illegal” under existing laws.

According to the Joan Mulholland Foundation (JMF), the day’s guest speaker Joan Mulholland risked her life repeatedly by participating in “over 50 sit-ins and demonstrations by the time she was 23-years-old.” And, she served as “a Freedom Rider, participant in the Jackson Woolworth’s Sit-In, the March on Washington, the Meredith March, and the Selma to Montgomery March.”

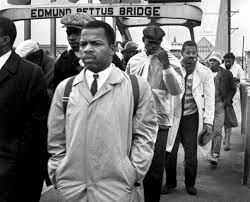

Defying the Jim Crow norms of the day, Mulholland’s actions led to her being “disowned by her family, attacked, shot at, cursed at, put on death row and hunted down by the Klan for execution.” Despite the threats to her life, however, Mulholland crossed paths and worked with “some of the biggest names in the Civil Rights Movement: Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, John Lewis, Diane Nash and Julian Bond.”

In addition to her receiving numerous civil rights awards, Mulholland’s story and experience have been highlighted in award-winning documentaries including “An Ordinary Hero,” PBS’s “Freedom Riders,” “Standing on My Sister’s Shoulders,” and the ground-breaking documentary film “Eyes on the Prize.”

‘Work Together to Make Freedom Happen’

Stepping to the mic, Mulholland – sporting a fiery red hair scarf and black t-shirt emblazoned with super-sized images of MLK – sparked the audience with humor, regional color, shocking details, advice for activists and inspiring stories of facing down harrowing threats “without fear.”

“Like my ancestor said, ‘I’m still kicking, just not as high!” Mulholland began pluckily in a deep Georgia southern accent.

“And, yes, we have to work together!,” she added, before giving a shout-out to the sorority women from AKA, who helped organize the day’s workshops and activities. Her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta – or the “Crimson & Cream Deltas” – used to work side-by-side with the “AKA ladies in pink and green” during the Civil Rights Movement.

With the crowd primed, Mulholland launched into the dangers and sacrifices she and other activists confronted. “When the Sit-ins started, we had folks who were roughed up, dirtied-up, [But] they came back to the gathering place to get us cleaned up.”

But, there’s a place for everyone in the movement, she stressed. “I’d say there were as many people on the front lines as there were having their back,” she said. “If you don’t feel like you can be on the front lines taking on those risks, drive a car to drop people off. Blend into the crowd, as what we call a ‘spotter.’ I did that a few times. People have to eat. Cook! If they’re from out-of-town and need a place to sleep that won’t break their bank accounts and you’ve got a spare bed, let ‘em use it! Work together to make freedom happen. And don’t be afraid. Fear will paralyze your brain and keep you from thinking of what you need to be doing in the situation."

The Power of the Press

“I say you take your issues to the lunch counter or to the street. The lawyers take them to the court. But the press takes your issue to the world. Never forget the power of the press!,” Mulholland advised. “And when stuff starts flying, those reporters are in every bit as much danger as you are. In fact, sometimes the reporters are attacked first because the attackers know they take the story to the world,” she continued.

“At that Woolworth Sit-in in Jackson Mississippi, the picture of that taken by a reporter, a photographer, is the most used Sit-in photo in the world. And that group was the most integrated Sit-in – Black, White, and this one professor was a Native-American tribal member. We didn’t have any Asian-American students that semester, so that was missing. But, we did pretty good. And before we sat there, one guy had been pulled off his stool and got kicked and he had blood coming out of every part of his head and the guy who filmed that, a local TV man, he was knocked to the floor and his camera broken, they tried to stop it, stop the word from getting where they didn’t want it.”

Actions Can Change Attitudes

However, “your actions can change people’s attitudes,” Mulholland stressed. “The guy who took the picture of that Jackson Woolworth Sit-in, I was talking about, he was going to the same high school as those kids behind us taunting us and hitting us. When he came in, his sympathies were with his buddies, including the guy who lived just three doors down the street from him.”

“Well, he was doing his job,” Mulholland continued. “He got permission to stand on the lunch counter to take pictures of us. And by the time he was through, three-hours later, his heart was changed. He’d seen what his buddies were doing and he saw us taking it non-violently. And he supported the demonstrators. And the power of the press? A kid from a rival White high school, segregationist too, he saw those pictures in the paper that night and his heart got changed. That’s the power of the press. Never forget it whatever you’re planning.”

More to Do Than Just Marching

“Now, you had a march today, in spite of the weather. But there’s still more to do,” Mulholland prodded. “I say, my generation took care of segregation under the law. But that’s not the underlying discrimination. It’s still alive and well. And we recognize it in so many forms today, more than we ever did before.”

“It’s not just the color of skin. It’s native language, where you’re from,” Mulholland continued. “Even in the United States, us southerners get a little picked on, you know? Us White southerners? They see us as the Devil incarnate sometimes. But, it can also be physical disability, gender [identification], religion. All these forms of discrimination, we didn’t really pick on back then. But, they’re out there and you’ve got to get it together and do something about it folks. I know some of you are.”

Detailed planning is essential for any protest movement, Mulholland emphasized. “You’ve got to find people who agree with you on the issue. You’ve got to get together a plan of action, a specific plan of action, not just, ‘Oh, we’ve got to march.’ You’ve got to plan when and where. You’ve got to have your lawyer’s phone number – maybe even written on your wrist – and you’ve got to know the power of the press. Don’t forget them. And you’ve got to get out there and do something.”

But, you have to be prepared for folks getting arrested, Mulholland warned. “You know, maybe you’ve got to rustle up some bonds money if it’s a really rough situation. We had Medgar Evers and the NAACP, which he was a part of down in Jackson. Medgar got involved with the NAACP and he raised a little bit of bonds money for us. C.O.R.E., the Congress of Racial Equality, was behind that.”

Newly Revealed Support from Secret Sources

Mulholland then recounted a remarkable story about finding out there were secret supporters to the Movement from unexpected quarters. “And, I found out just a few years ago, I was on a cruise somewhere, and was sitting at this table with a woman, and got to talking,” Mulholland recounted. “Well, I found out that the White women in Jackson, the liberal White women, they were getting money together for us, and they were passing it on to their maids for the Movement. I never knew that. Not till just a few years ago. Only took, you know, fifty-something years to find that out. [Laughs]. But, there are a lot of things going on that you’d never suspect. So we owe it to them."

Making ‘Good Trouble’

Before concluding, Mulholland didn’t want to forget one key detail she'd left out. “And, oh yeah, I was arrested probably half a-dozen times if you count being jailed in contempt of court and arrested. And, you know, I wasn’t booked, but I was locked up down in Baton Rouge. And, I got in a lot of ‘Good Trouble,’ [Laughs] referring to the late Georgia congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis’s famous battle-cry for protesting unjust laws.

“And that Good Trouble man? John Lewis?,” Mulholland continued, her southern drawl accentuated. “Oh, he was a southern gentleman. Did you know southern gentlemen always hug, right? [To the audience] We got some southern gentlemen out here who like to hug? [Laughs]. Right! And every time I saw John, I got my southern gentlemanly hug. Sometimes, he could be speaking at a big convention somewhere, a keynote speaker or something? I got the hug. Sometimes I walked up to him and sometimes he said, ‘Joan, I need a hug.’ Well, now he’s gone. And my 'Hug Man' now – and I informed him of his role – is Congressman Benny Thompson. We graduated from the same college just a few years apart. And every time now I see Benny, you know, the Chairman of the January 6 Committee and all that? I get my hug. We’re friends across all barriers, yeah. So, gentlemen, hug the ladies in your life. Okay, enough of me.” [Applause].

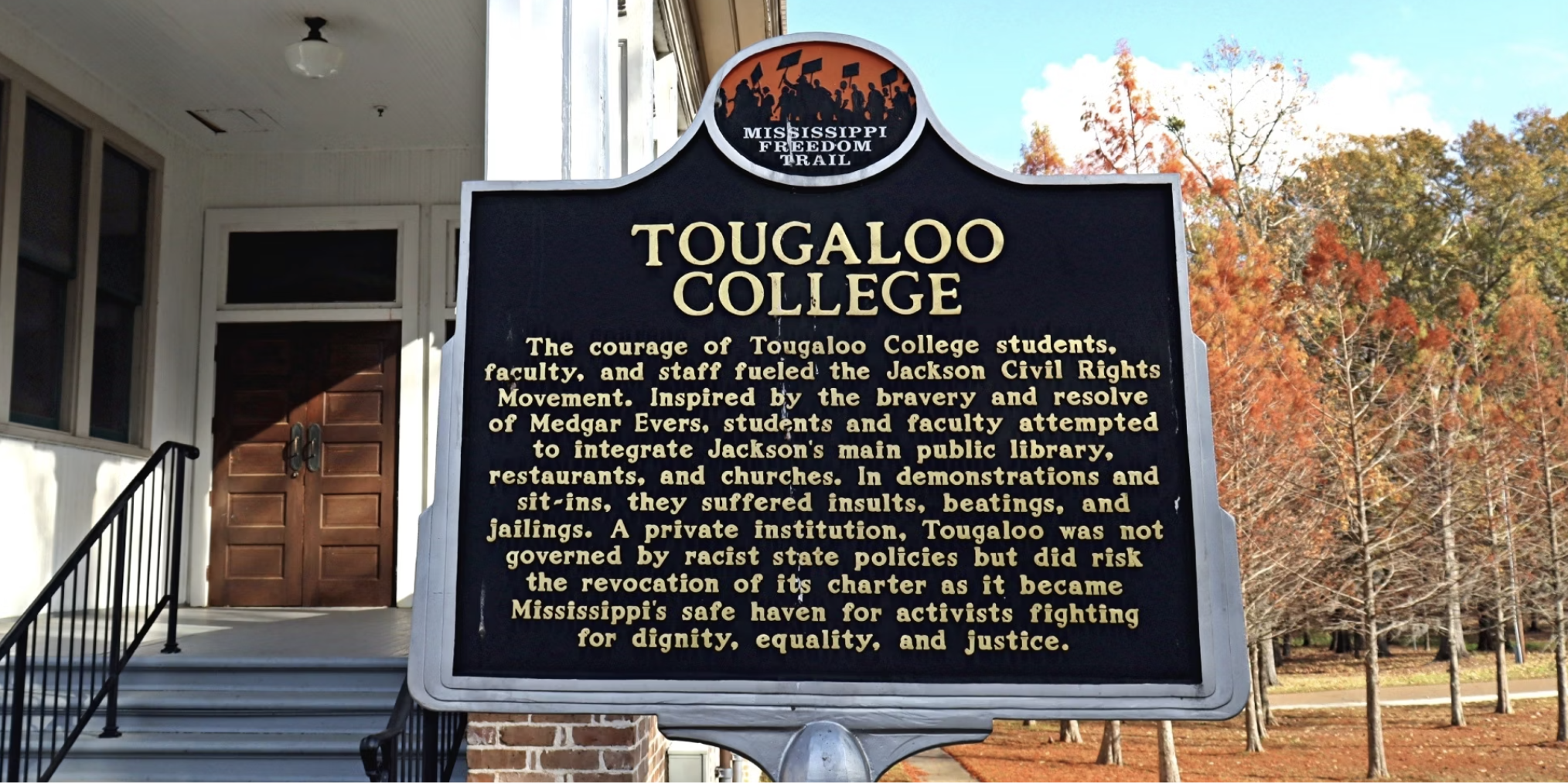

Before finishing, Mulholland took a few audience questions, each one allowing her to illuminate her storytelling and vision more dramatically. As the first White student to integrate the historically Black and segregated Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 1960, Mulholland alluded to the hatred aimed at her choice to transfer there after her freshman year at Duke University. “Tougaloo was the only [Black] school in the entire state of Mississippi that was actually accredited, like if you wanted to go to graduate school, or transfer to another college?,” Mulholland said. “Tougaloo was it. So, I applied to Tougaloo.”

But then her own all-White high school in Annandale, Virginia started in with the hate. “Then I got this letter in the mail. ‘We heard from Duke University,’ – where I went my freshman year, and got involved with my brothers and sisters, and the Sit-ins, though that wasn’t the plan – ‘And, we heard from Duke University, but we never heard from your high school.’ You know, it was out in Annandale, Virginia, you know, out in the boonies? [Laughs] And I called Annandale and talked to the counselor and she said, ‘Well, we’re not going to send your transcripts to THAT school.’ Well, I knew what she meant by ‘THAT school.’ So, I called Tougaloo and told them and they understood what was going on and they said, ‘Well, we’ll accept you on your Duke transcripts.’ So, I went to Tougaloo and took the Freedom Rides to get to Mississippi.”

But, for taking a racially integrated Freedom Ride bus to go to her new school, Mullholland was arrested and sentenced to jail at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, the notorious Parchman Farm, where she was placed in the Death Row cells.

Audience member Nikki Graves Henderson (spouse of Edwin Henderson II, founder of the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation), then asked an insightful question. Introducing her 9-year-old grand-daughter, Henderson said the two were wondering what Mulholland was doing at age nine to change the trajectory of her life toward the Civil Rights Movement.

Mulholland’s response was perhaps her most gripping memory from childhood. “Well, I was actually 10 – Or, maybe I didn’t turn 10 until that fall – But, I was down visiting my grandma in Okonee, Georgia. And I had the same playmate every summer. And we’d go down. And we decided to sneak off and go where we weren’t supposed to.”

“A dirt road to the colored section of town,” Mulholland continued. “Now this whole town was just real poor. It was a company-owned logging town. And the houses there were even worse than they were in the White section. And folks saw these two little White girls – and this was before Emmett Till — they saw these two little White girls coming down the road and they just made themselves scarce. Disappeared behind their houses or in their outhouses, or wherever. And, so that was creepy enough.”

“But, then we got to the school, for the colored students,” Mulholland said. “It was a one-room shack without an ounce of paint on it. The door was ajar. You could see the potbellied stove for heat. No glass or screen on the windows. Just wooden shutters. It was pitiful. And no electricity or running water, of course. And I knew, out on the other end of town was the fanciest building for miles around. A brand new brick school for the White kids with all those fancy amenities. And I knew it was not what we learned in Sunday school about ‘loving your neighbor as yourself and treating people the way you wanted to be treated.’ And, I remember, I couldn’t put it in words, but when I had a chance [I'd] help make the South... the best that it could be. And to seize the moment. And that came with the Sit-ins.” [Applause].

And, to respond to today’s political anxieties and fears, Mulholland had one prescription. “Vote!”

Following a rousing standing ovation for Mulholland, participants were placed into break-out workshop discussion groups on the day’s theme of “Mission Possible – Protecting Freedom, Justice, and Democracy: What Can I Do?” In a plenary session, Inga Watkins, JD, of the Social Justice Committee facilitated discussion of what the break-out groups identified as items-for-action.

The day concluded with a group singalong of civil rights folk standard “If I Had a Hammer,” closing remarks from Social Justice Committee Chair Phil Christensen, and perhaps the best-known anthem of the Civil Rights Era, “We Shall Overcome.”

Now, on to that 'Good Trouble'...

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion