Earth Day: A Story Buried… and Exhumed

On this Earth Day, April 22, 2024, – the annual celebration of the environmental movement and the need to protect Earth’s natural resources for future generations – let us celebrate how far the ecological sciences have advanced since the very first such day 54 years ago, in 1970.

Despite such scientific progress, however, many known environmental health hazards – think “forever chemicals” in the soil, “microplastics” in the waters, and “toxic airborne particulates” from wildfires – remain elusive to our full understanding and to public awareness.

Nevertheless, a look back at what motivated some of the earliest Earth Day activists in the late 1960s may help refresh our motivations today to protect our planet for future generations.

Earth Day’s Idealistic (and Somewhat Mischievous) Origins

With its scientific focus on the hidden toxic nature of pesticides in the environment, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), is often credited with launching the “modern environmental movement.” On many American college campuses throughout the 1960s – long before the EPA came into existence – young Baby Boomers began questioning not only why their parents’ generation had made a mess of Vietnam and Civil Rights, but also of the air, the water, and the land.

In January, 1969, the junior Senator from Wisconsin, Gaylord Nelson (D-Wisc.), witnessed the horrendous effects of a massive oil spill off Santa Barbara, California – already beset by the smoggy air that had become the Golden State’s norm prior to the passage of the federal Clean Air Act (by the end of 1970.) “Inspired by the student anti-war Movement, Sen. Nelson wanted to infuse the energy of student anti-war protests with an emerging public consciousness about air and water pollution.”

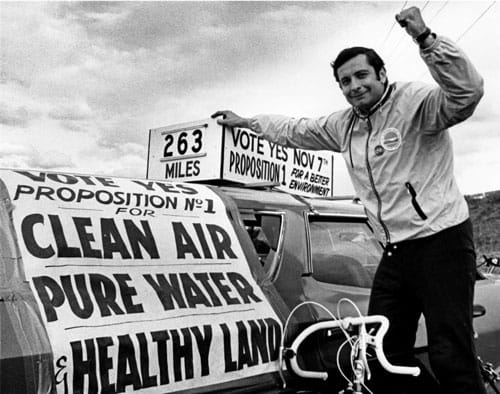

According to Earthday.org, Nelson “announced the idea for teach-ins on college campuses to the national media, and persuaded Pete McCloskey, a conservation-minded Republican Congressman [from Calif.], to serve as his co-chair.” Nelson then recruited a young activist, Denis Hayes, to organize campus teach-ins and to “scale the idea to a broader public.” They chose April 22 – a weekday falling between Spring Break and Final Exams – to maximize student participation. Soon, Hayes built a national staff of 85 to “promote events across the land” and many organizations joined in the promotional and educational efforts.

With national attention on the first “Earth Day,” a remarkable 20 million Americans, “then 10 percent of the U.S. population” – are believed to have taken part in some form. “Groups that had been fighting individually against oil spills, polluting factories and power plants, raw sewage, toxic dumps, pesticides, freeways, the loss of wilderness and the extinction of wildlife,” had joined together in common purpose.

Hard to imagine today, the first Earth Day “achieved a rare political alignment,” according to Earthday.org, “enlisting support from Republicans and Democrats, rich and poor, urban dwellers and farmers, [and] business and labor leaders.”

By the end of 1970, the first Earth Day “led to the creation” of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the National Environmental Education Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act.

The Story of the Buried Car and Why It Was Dug Up Again

But there’s a more colorful story to the Earth Day founding than this.

It also involved the ritual burial of a "brand-new automobile" and its subsequent exhumation.

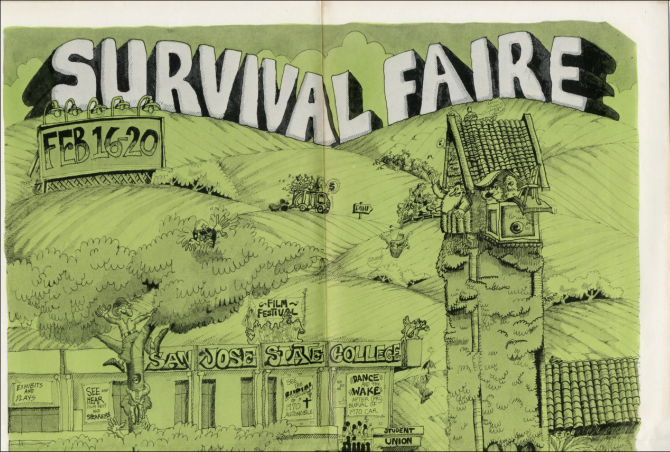

In February 1970, on the campus of San Jose State College in California – which Earth Day’s founder Gaylord Nelson had attended – pro-environmental students organized a one-week “ecology extravaganza” dubbed “Survival Faire,” according to journalist Sam Whiting of The San Francisco Chronicle.

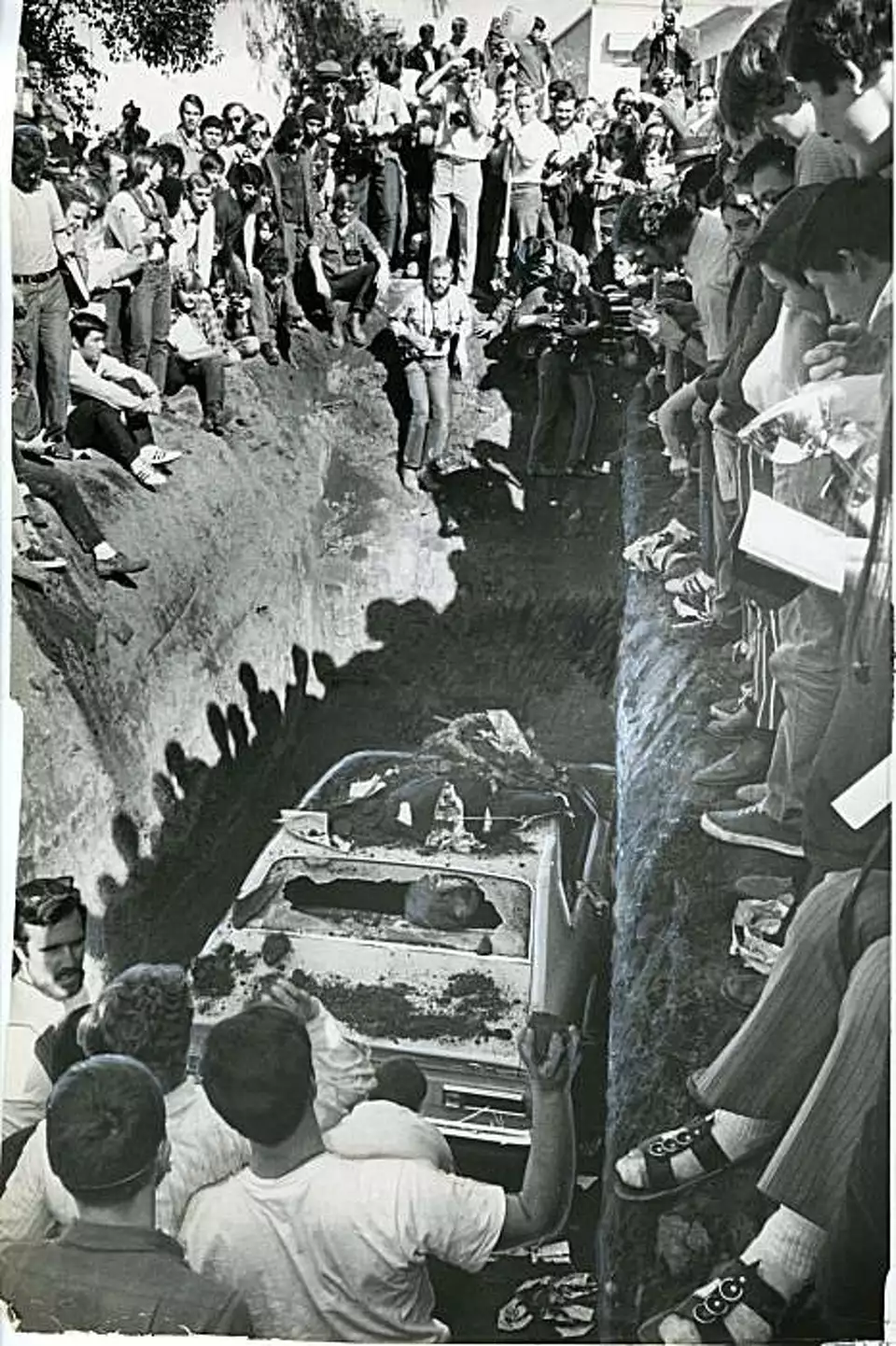

Today, the festival is known primarily for one particular “signature action” – a ritualized performance of political theater involving “a bunch of students who bought a brand-new, never-started Ford Maverick [and pushed] it from the dealer’s lot into the center of campus, where it was ceremoniously buried in a pit, 12 feet deep.”

Why?

“The elaborate funeral procession was conceived of as an anti-internal combustion, anti-smog statement to cap off the weeklong fair, which itself resulted in one of the first environmental studies departments to be established at any university in the nation,” Whiting reported. “As a publicity stunt, the car burial was brilliant, gleaning way more Bay Area press coverage than the comparatively subdued first Earth Day, which followed it on April 22, 1970.”

"Ken Kesey would have been proud of it. It turned into a real theater of the absurd," recalled the student organizer, Peter Ellis, as he stood on the car's ancient burial ground, which is directly under the new Cesar Chavez Plaza at the entrance to the Student Union,” Whiting reported.

The following excerpt is drawn directly from Whiting’s reporting for the San Francisco Chronicle.

“The car event came out of a class project in Humanities 160 taught by John Sperling, a tenured professor who developed some creative notions about higher education. One of them was the University of Phoenix, the pioneering online university that Sperling left San Jose State to start.”

“Now 89, Sperling does not answer questions about the controversial for-profit online university that made him one of the wealthiest people in America. But he still answers the intercom at his Cow Hollow home and is happy to come downstairs and invite in a stranger who carries as letters of transit two photos of the automobile funeral he inspired 40 years ago [article published April 20, 2010.]”

"This was part of the whole movement for the first Earth Day, and everybody in the whole university was watching them," says Sperling, proudly looking at a picture of students surrounding the Maverick. As the professor, he was hands off, meaning he did not actually help push the automobile from the lot in Los Gatos, where it was purchased.

"I was there for the car's arrival," he says. "They put it in the middle of campus with velvet ropes around it. It was really quite a handsome thing."

Humanities 160 was an upper-division course populated by 19 students, drawn largely from the art department. "When you have artists with you, it always adds to things, and it just kept snowballing," says Ellis, 63, now a community crime prevention consultant living in Alameda. "We were sitting around and somebody said, 'We ought to bury an engine.' Before the night was over, we were going to bury a Dodge Charger, a muscle car."

The group had no leader, but because of his graduate student status, Ellis became a point man.

"I didn't have a title," he says. "Those were hippie days." Still, they needed money for the Dodge, so they sold shares in the car and raised $30,000, Ellis says. But because these were hippie days, they spread it around Survival Faire participants and in the end there was only $2,500, which reduced their buying power from a Dodge to a Ford when they visited the car lot the weekend before the fair was to start.

All during the Survival Faire, the Survival Car - as the two-door "hugger-orange" Maverick was dubbed - was on display waiting for the grave, alongside a prototype BART car, representing the future. "The idea was to symbolically bury the notion of cars and gasoline," recalls Dan Freedland, one of the pallbearers on Survival Day, the Friday finale.

Anticipation was so high that The Chronicle pulled reporter Paul Avery off the case of the Zodiac killer and sent him down to cover it. He arrived to find a standoff. A group of students representing the poor and disenfranchised didn't see the point of burying a perfectly good car. If you are going to do that, why not give it to them to find a better use for it?

A voice vote was taken, and the bury-the-car faction won, at which point the faction that wasn't going to get the car to drive made sure that nobody else would, by jumping on its roof.

With six or so students riding on the roof of the Maverick, "it was pushed through downtown San Jose in a parade led by three ministers, the college band and a group of comely coeds wearing green shroud-like gowns," read Avery's report under a bold headline: "How They Buried a Brand New Car."

"As the local citizenry looked on from the sidewalks," Avery's report continued, "the students marched by at a slow funeral pace set by the band which played a selection of songs in dirge styles."

The same student-driven backhoe that had dug the grave covered it over, and a lawn was planted on top.

The next school year, Ellis was contacted by proponents of a ballot measure to bring public transportation to Santa Clara County. The car that had been buried as a publicity stunt was now to be exhumed as a publicity stunt. It would then be crushed into a 36-by-24-inch block and promised as a cornerstone of the county's first rapid transit station.

Ellis was by then pursuing his doctorate at the University of Michigan and couldn't attend, but "300 students applauded soberly as the car was brought to the surface by a back-hoe machine," read The Chronicle report.

The ballot measure failed, and the car was dragged away. In the mid-1970s, Ellis made a pilgrimage to the transportation yard and found the remains of the Maverick off to the side of a building. "There was nothing left of that car," he says. "It was scorched into a rusted cube."

Humanities 160 is still offered, though car burial is no longer worthy of academic credit.

"I thought it was a rousing success," Sperling says, "and they all got A’s, obviously."

The Spartan Daily Looks Back on ‘Survival Faire’ and the Car Funeral

For Earth Day 2008, reporter Tara Duffy of San Jose State University’s Spartan Daily interviewed a “witness of the Survival Faire and the car funeral” of February 20, 1970. She met with Gary Hobbs, who graduated from San Jose State College with a degree in biology.

The automobile buried in the “Car Funeral” was “a 1970 yellow Ford Maverick.” It was “buried next to the Student Union and was bought by student donations for $2500,” according to a Spartan Daily report of Feb. 16, 1970. “Members of the Kappa Sigma fraternity pushed the car from Paul Swanson Ford in Los Gatos to the university.” And, the “car was never started.”

The idea originated from “a humanities class,” Hobbs recalled. They “wanted to get involved in Earth Day” and wished to “do something a little outrageous.” So, they came up with the idea of pushing a “brand new car” down here to San Jose and burying it in the ground.” They made a poster to that effect and spread that poster around.”

What really got people going, Hobbs remembered, was everyone asking “Are they really going to bury the car?” The goal was to promote mass transit. Excitement raged on the campus of 27,000 students, Hobbs remembered, and the topic of burying the car led to wider environmental discussions and students wanting to register for environmental coursework. “It brought a lot of awareness.”

Hobbs's Stance on The Car Funeral Controversy

Soon, however, significant controversy arose over whether burying a brand-new car was a good idea. Ironically, the objections were not over the environmental effects of disposing a new automobile in the grounds of the campus, but on the wastefulness of the symbolic act. Given poverty and dislocation, weren’t there better uses for the fundraised monies?

As a teacher, Hobbs remarked how surprised his young students are when they hear about the Car Funeral. “They can’t believe it,” he said. Nor do many older people with whom Hobbs raises the subject. “I think it was something that gained worldwide attention… that a bunch of crazies were going to bury a brand-new car in the ground.” But, he credits the ceremony with raising environmental awareness at the time.

And what side was Hobbs on? Surprisingly, he was opposed to the car burial at the time. “The Environmental Information Center had a booth in the Student Union,” Hobbs recalled, “and we were against the burial of the car. And we collected 5,000 signatures against burying that car. And the day they were going to bury it, I had to stand on top of that car and deliver a short speech saying I don’t think [we should do this] and then we put our papers of petition in the glove box [and they were buried] along with the car.”

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion