Falls Church’s Public Library Strengthens Policies Against Censorship

Are you concerned about the waves of book-banning across the nation and in Virginia? Could they be coming soon to the Mary Riley Styles Public Library in the City of Falls Church?

The Falls Church Independent spoke with the Executive Director of the Virginia Library Association (VLA), Lisa Varga – Library Journal’s 2024 Librarian of the Year – and to the Acting Director of Mary Riley Styles Public Library, Marshall Webster, about concerns over the increase in politically motivated book-banning efforts, the responsibility of public library collections to represent a multiplicity of viewpoints, changing library policies on petitions, and the centrality of the “freedom to read” principle for modern librarians.

Waves of Book-Banning

According to the American Library Association (ALA), bills that could harm libraries or limit the books and services they provide were proposed in 27 state legislatures across the nation so far just this year. “Nationally, 4,240 different titles were targeted for censorship last year, compared with the previous record of 2,571 in 2022,” per Axios.

Unfortunately, the Commonwealth of Virginia has been a key battleground over what sort of material public school libraries and public libraries can make available to students and patrons. “Nearly 400 book titles were targeted for bans in Virginia libraries last year, among the most in the nation, according to new data from the American Library Association,” Axios reported March 4. And, “some of the most targeted books deal with themes of social justice, discrimination and inequality, which can diminish access to viewpoints and cause harm, according to the ALA.”

Increasingly, public libraries for all – and not just public school libraries for students – are being targeted by petitions calling for taking books off the shelves. According to the ALA, the number of titles targeted for removal has risen 92 percent since 2022.

Lisa Varga’s View as Executive Director of the Virginia Library Association

How worried should we be in Falls Church about the book-banning efforts we’re seeing across Virginia and the nation?

“Everybody should be concerned about the impact of trying to take books off the shelves and the way some have been going about it because it’s government overreach,” Varga – who earned an MLS in Library and Information Science degree from Rutgers University before taking charge of the VLA – said. When public libraries are pressured to censor people’s viewpoints or to deny access to First Amendment-protected materials, people’s rights are at stake.

“The public library is a public good. It is here to meet the needs of all residents, regardless of age or income,” Varga said. “It is meant for people to come and be lifelong learners, to get access to information they don’t have the finances to access in most cases. For example, there’s not a lot of discretionary income people can put toward books these days. So for people who may love audiobooks, who can’t afford an Audible subscription, your library offers you free access to Libby and Hoopla, where you can download and listen to your heart’s content.”

For Varga, who runs the VLA from her home office in Virginia Beach, Virginia’s public libraries are chartered to serve the diverse needs of all the members of the public.

“We’re getting very creative,” Varga said. “We evolve to meet the needs of our communities. So, for example, in the city of Virginia Beach we circulate surf boards. That’s not necessarily needed in some of the other communities in our state, so they circulate other things that are more relevant, like maybe in Harrisonburg, they’ve got more hiking kits or bird-identifying items. You know, we meet the needs of our communities because we’re members of our communities and pay attention to them.”

With fewer book stores in neighborhoods, it’s harder for people to experience the thrill of chance discovery where one happens upon a book that might change one’s life. “That’s why Jefferson-Madison regional libraries just put a book vending machine out in their area so we can have more of the serendipitous [experience.] At Virginia Beach, we’ve got Book Bikes, so while tourists are exploring the beach we’ve got librarians going up and down so people can have beach reads. Because we know the benefits of reading. It helps with your heart rate, it helps with your focus. It helps with your concentration – aside from just learning.”

Varga is concerned, however, that the book-banning campaigns she’s been seeing across Virginia are less about protecting children from inappropriate materials – as petitioners calling for “parental control” over distributed materials often emphasize – than about suppressing minority viewpoints and access. “We do have a small and vocal group of people demanding the removal of titles that specifically target underrepresented communities, like LGBTQIA or BIPOC individuals,” Varga said. “It’s much more a statement about the state of democracy than it is about individual books. And so it’s very concerning that anyone wants to pressure a public institution into removing titles they disagree with. The majority of these people who oppose these books, by the way, haven’t read them.”

“Obviously, protection of children is paramount,” Varga emphasized. And it’s vital that libraries allow people to question the appropriateness of what’s being circulated. “Challenges to materials and reconsideration are part of a healthy library collection,” she said.

But, many of the petition drives Varga has seen are irresponsible. “We want people to come in and talk with us. But what’s happening is that people who have concerns are not necessarily coming in and talking to librarians. They’re waging online social media campaigns, or showing up to school board or public Board of Supervisors meetings and making a big production in the hopes of getting attention. And what’s getting lost [are the rights of] people who want or should be able to access these books without someone else deciding what they can and cannot read… You know, we’ve had instances from around the country where people who don’t even live in communities sign up to speak at meetings, get up there and read a passage out of context and then walk away and let the dumpster fire go and that creates a lot of mistrust, it has very little transparency, which is what we want to have in our well-rounded society.”

Varga has noticed some backlash against more extreme book-banning efforts even in more conservative areas of Virginia, however. “I think one fascinating thing that came out of the controversy in Front Royal is that the Chair of the Warren County Republican Committee came out and said, ‘Wait a second – this is government overreach.’ Initially, he had been an advocate for removing the books he felt were pornographic or obscene – and these are words that should not be used to describe these books – [And even] he came out and said, ‘This is too much.’”

And Varga has not shied away from publicly highlighting the soaring costs arising from the high volume of book-banning petitions. “It does create a hostile work environment for some people, especially if you have these repeat petitions coming through where people haven’t read the book but your school system is now required to spend [so much].”

In a legendary move, Varga calculated the staff hours and hourly pay needed to handle a single petition and then presented the petitioners with a bill for the costs at a Virginia Beach School Board meeting. “I showed up… with an invoice, because I also noticed that a lot of people were getting up at School Board meetings and saying things like, ‘My name is so-and-so and I’m a taxpayer.’ And they were against books. And I thought, I’m a taxpayer too, and I read books. So, I showed up with an invoice and I said, ‘You owe the taxpayers $400,000, because this is a waste of time and energy. You already have experts in the field making these decisions. And, we are good stewards of tax dollars. You’re making it impossible for people to do their work.”

“What really drives me crazy are people who latch on to the concept that there is any book in the library that's pornographic or obscene. No books meet those criteria. And that’s because you’ve got professional librarians who’ve been doing this for decades who have their master's degrees, who are trained in collection development and management and understand age-relevance and age-appropriateness and they select items based on criteria that passes a First Amendment test. And so when you come in and say, ‘I don’t want a picture book that depicts a family where both parents are dads,’ well, fine – don’t pick up the book for your family. But don’t tell other people the book can’t be there and don’t tell other people who are “two dads” they can’t be represented.”

For Varga, the “freedom to read” principle is not only a central tenet for librarians – and embraced by the ALA and the VLA – it’s a core principle of democracy. “I think the importance of the ‘freedom to read’ is that if we're really intent on being a country where we celebrate all of our differences and find ways for us to come together, reading is vital. Learning is vital…. And why would we limit what kids want to read? We should be able to have them see a variety of people, places, families – all of these things represented. And we should be able to have conversations as families, as parental units about what these kids are interacting with. And, I mean, if you’re not talking to your kids about what they’re seeing online, you’re missing out, because they’re seeing a lot of things that are way more inappropriate than anything they’re going to find in a book.”

Marshall Webster’s View as Acting Director of Mary Riley Styles Public Library, The City of Falls Church

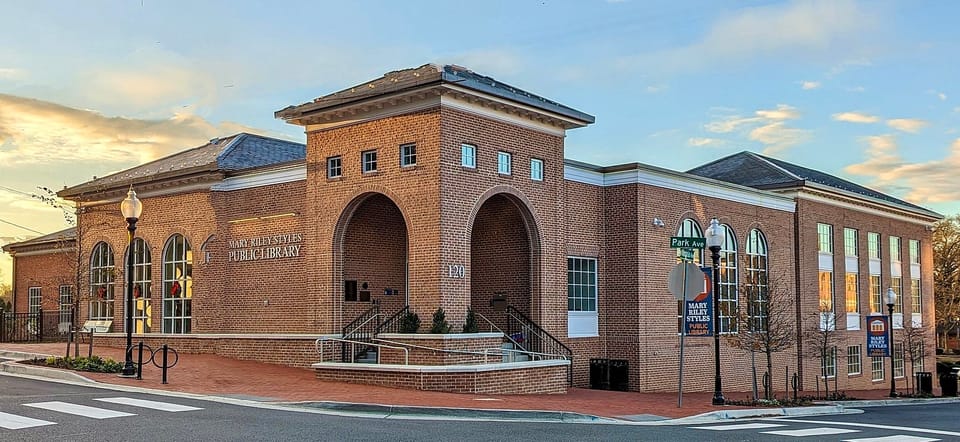

At 120 N. Virginia Ave., in the City of Falls Church, Marshall Webster has worked at Mary Riley Styles library – the city’s sole public library – since June, 2001. “It’s a very nice place to work and a very supportive community,” he said. He’s currently serving as Acting Director of the library since the library’s permanent director, Jenny Carroll, is serving as Interim Deputy City Manager.

In keeping with the “freedom to read” principle, Webster emphasizes the importance of allowing library users to make their own choices. “Our goal is to provide as many different perspectives and to give people the opportunity to learn and discover and to make choices themselves,” Webster said. “So, I think the only way to do that is to give people the opportunity to borrow a wide variety of materials. But, I understand that it’s very sensitive and people have very different opinions. But, at the end of the day, we want to give people as much choice as possible.”

Fortunately, from Webster’s point of view, Mary Riley Styles Public Library (MRSPL) has not yet been targeted by organized book-banning efforts, though he acknowledged that, “the climate in the last few years is a little different” around Virginia. The political pressure “is not so much in this immediate area,” he said. “But I think the state has felt it in different locations.”

Webster credits Lisa Varga and the VLA for the help they’ve given local Virginia libraries facing petition drives. “They have a lot of processes they’ve developed to help support librarians throughout the state if they do feel challenged.”

But Webster is not opposed automatically to citizens who wish to challenge circulating materials. The library’s collection development policies and their fielding of reconsideration requests just need to be balanced so that petitioners’ efforts don’t infringe on people’s “freedom to read” rights. “People can have different reasons for questioning a book. So you have to be neutral when you start – and read what their concerns are and take them seriously. But, we do advocate for the ‘freedom to read’ and the freedom to access materials. And that’s our starting point which is specified in the policies.”

Webster acknowledges that Falls Church is politically less inclined toward library censorship than other parts of Virginia. Since he’s only been serving as Acting Director since September, 2023, he’s seen no petitions against library materials. In fact, the only one he can recall was around 2019 when a children’s book by Geronimo Stilton was challenged because “maybe it was a little sexist.”

Nevertheless, Webster indicated that given the shifting political landscape in Virginia, Mary Riley Styles adopted in June 2023, under director Carroll, new policies to ensure the petitioning process be more rigorous to ward off ill-informed book-banning petitions.

The updated “Collection Management Policy” is spelled out at www.MRSPL.org in the “About” section. It “specifies how we go about collecting materials,” Webster said. And, it also has a “section at the end for a request to review library materials. So, somebody could, if they wanted, request that we reconsider something for whatever reason. [And] it specifies how you would go about submitting that request and what the process is for review.” The form is a fillable, linked pdf that can be submitted online.

Updated Collection Management Policies

One of the “new requirements,” Webster said, is a set of questions essentially asking petitioners if they’ve done their homework before petitioning. “How did you learn about the material? Have you read, listened, or viewed the material in its entirety?” petitioners are asked.

Petitioners also must respond to: “What concerns do you have about the material? Provide citations and quotes including page numbers from the material. Please evaluate the material’s positive and negative qualities. How has the material been assessed in professional review sources? Please list the sources and provide citations. Who would be negatively impacted by this material and how?”

Citations are also required for the questions: “What age group would you recommend this material to? Are there alternatives to this material which MRSPL should consider?” Also, “Please include titles and professional reviews of the replacements and what action do you request that the Library Panel take?”

Petitioners are instructed about the review process. The library creates a small panel of staffers who consider the submitted petition and make a recommendation. “The petitioner is then notified of the determination within a period of time. If they wish to appeal, they can ask the Library Board serving the City of Falls Church for a second consideration,” Webster said.

While Webster said the policy updates of June, 2023 were designed to make it “a little clearer about how you submit a request for reconsideration,” it’s clear the intent of the new procedures is to prevent a flood of obstructive and ill-considered petitions – especially from non-residents of the City Falls Church. “So, we did change it a little bit,” Webster said. “In order to be able to request a review, you have to be a [Falls Church] City resident and a [library] card holder. And, we also say, ‘Only one form per household may be submitted.’

Webster continued: “And, a requester may have only one active form for the duration of the request process. The material being challenged must be read, watched, or listened to in full by the requester. The form must be completed in full before the review process. Responses may not be cut-and-pasted from other resources outside the requesters own work. The materials are evaluated within the context of the library’s collection management policy, including the ALA Freedom to Read Statement and Mission Statement. And then it goes into the whole review. But the main thing we added also was that once a decision is made the determination is good for another two years. So, someone can’t come back and submit another challenge for the same book, a month later, because it’s labor-intensive to keep going through these reviews.”

With all of that reading and form-filling to be done, at least there are book nooks and study spaces available for all in the city's local public library.

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion