The AI Experience at Meridian H.S.: Parent Coffee Reveals School's Adaptive Responses to Generative AI’s Disruptions

Now that AI’s here, seemingly for good, how should school systems respond?

At Meridian High School in the City of Falls Church, Principal Peter Laub, and IB Diploma Program Coordinator Josh Singer hosted “From Chalkboards to Chatbots,” a Dec. 11 Parent Coffee with a panel of teachers and students, designed to provide attendees with, as Principal Laub described it, a “state of the state” on “What the reality [of AI use] is in the schools,” what students and teachers are experiencing with it, and what the dialogue on AI with the School Board and the community "looks like"?

“This session provides valuable insights as our School Board develops comprehensive AI policies for Falls Church City Public Schools,” FCCPS wrote to describe the forum. “Whether you're a parent wanting to understand how AI affects your student's education or a community member interested in educational innovation, this conversation offers authentic perspectives from those experiencing these changes firsthand.”

The panel discussion reflected well on Meridian High School. Over the 57-minute discussion, panelists exhibited deep thoughtfulness, open-mindedness, and strong understanding of the challenges and opportunities posed by Gen AI in the school system. By posting the full session to YouTube – including a few critical remarks from attendees and students – FCCPS is making good on its commitment to “transparent communication about emerging educational technologies.”

The Educational Challenges Posed by AI: Background

Across the nation, the sudden rise of generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen AI) has radically altered the secondary school learning environment.

Since the explosive introduction in Nov. 2022 of Open AI’s ChatGPT – a shockingly effective machine learning and Large Language Model (LLM) chatbot, trained on much of the internet’s content to respond to user queries using predictive language algorithms that almost instantaneously produce useful responses to online queries – a global AI “arms race” has multiplied competitors in the field, from Anthropic’s Claude, to Google’s Gemini, to xAI’s Grok, to China’s Baidu, DeepSeek, and Moonshot AI.

Academic integrity issues have compounded with the rise of Gen AI, however. With an effectively written query, Gen AI tools can now research and “write” just about any sort of text – a major research paper with citations, a news article, a bulleted text, an editorial, a paragraph analysis, an historical speech, etc. And it can do so when prompted to use "the language a high school student might use.” Since Gen AI is only in its developmental stages, however, the responses provided can be prone to errors and “hallucinations.” Users who don’t fact-check responses are at risk of violating ethical or academic norms and embarrassingly sabotaging their own efforts.

With easily accessible and often free Gen AI tools available online, school systems, teachers, parents, and students, are grappling with a number of major challenges arising from the new technologies. School boards are attempting to ramp up new district-wide AI school policy guidelines. Teachers are concerned about students cheating or taking shortcuts with AI, or relying on AI to perform the “critical thinking” pupils are supposed to be developing. Students are worried about how to use the new AI tools to navigate their daunting academic workloads, while not falling afoul of plagiarism rules or falling behind other students competing for high grade-point averages critical to college applications.

Panel Discussion

Principal Laub framed the topic for the panel discussion: This is "a conversation with some students and teachers here at Meridian High School, about the state of artificial intelligence, in particular Gen AI tools, in … the intersection of the world, the classroom, and the teaching and learning environment.”

With a brief slide show, Laub provided historical context to earlier technological challenges that appeared to threaten traditional academic practices. New educational technologies have tended historically to cause “freak outs” at first, Laub said, but over time, educators adapted constructively to use the new tools for enhanced learning. Socrates, for example, fretted that the advent of writing itself hindered students from learning based upon recitation.

When Laub was a freshman in college, the new internet search engine Google went public on Sept. 27, 1998. Google’s “birthday” was something he was unaware of at the time, unsurprisingly, since few were then aware of what the company's innovations might foretell. At that point, he said, “I still had to go to a computer lab if I wanted to access the internet and do my schoolwork.” By the time he graduated, Laub said, Google had evolved to become something “I could use to help me with my work.” Within just a few years, Google would “rock the education world,” because “suddenly everybody had access to the answers.” Though the world of education was shocked and resistant at first, Laub argued, today “Google hasn’t gone anywhere, and I can’t imagine a world in which we [and] these guys [points to student panelists] don’t use Google.”

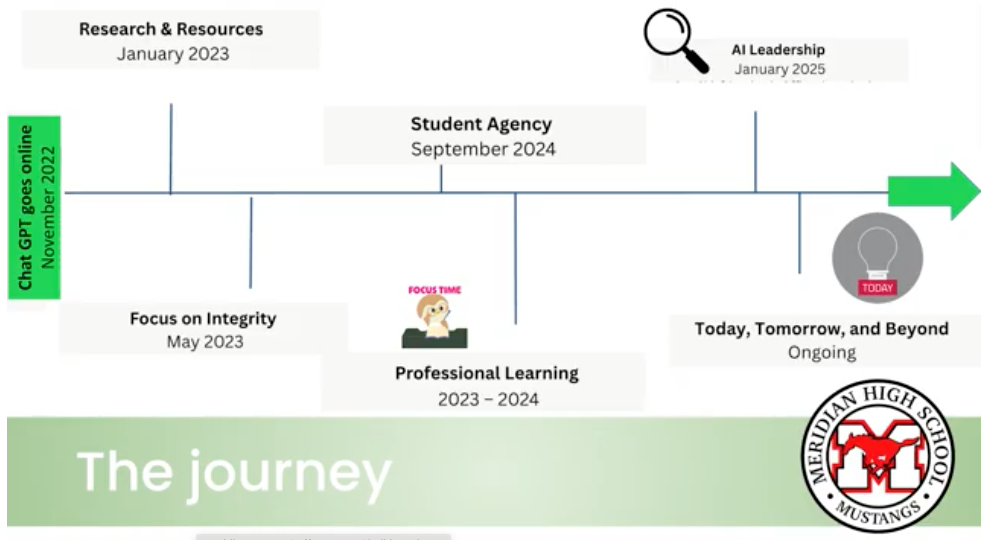

After recommending several articles exploring how today’s students are affected by the rise of recent online technologies and Gen AI tools, Laub projected a graphic outlining all the work Meridian and FCCPS have done to prepare guidelines on academic integrity and the use of AI in the school system.

“We’ve done a lot of work,” Laub said, “I’m seeing some familiar faces from parent coffees. You've come and heard us talk about academic integrity and how the Gen AI tools have really shaped our work with academic integrity. We've done some professional learning with our teachers to improve their abilities to use this in their classrooms and to help teach students. We've [also] empowered some student agency with this, and you're gonna hear from them, today…. I know our School Board is looking at this [and] our school division is looking at AI in the school. So today is … where you get to listen to these folks [points to panelists] and [hear] what the reality is on the ground."

Moderating the event, IB Program Coordinator Singer introduced the panelists – Students: Aiden Harper (Senior), Henry (Senior), Jillian (9th Grade), Ella Humphreys (Junior); Teachers: William Snyder (Computer Science/IB Career Path Coordinator), Jan Healy (World History/Business/Theory of Knowledge), and Jared Peet (World History/IB Theory of Knowledge).

How Students and Teachers are Using Gen AI

“What are some examples of how you've used [AI] in your work here at school, whether as a teacher or a student?,” Singer asked the panelists. In their responses, the panelists revealed fascinating details about the opportunities Gen AI has provided for their learning and teaching.

“I just had my IB oral for Spanish. So I used ChatGPT to come up with questions I might get asked and then I can answer and I can talk into it and it'll give me feedback on what I said," said Ella Humphreys (Junior). "And then I also use Duolingo [which] has their own version of AI where it's like a FaceTime call with their Spanish-speaking bot, and then you get the same feedback. And then, I also use the generative part [of Gen AI] to make pictures because you have to talk about a photo in Spanish."

IB Theory of Knowledge teacher Peet, described teaching students how Gen AI basically works and how to think critically about its potential risks. “In my IB Theory of Knowledge (TOK) class .... we talk a lot about: ‘How we know what we know.’ So we've been looking at algorithms and the purpose of algorithms…. and thinking about how it can create echo chambers.... So, one example is we had students pull up ChatGPT.... And, a lot of times, ChatGPT will prompt you with like, ‘Which answer do you like better?’ .... So we talked about how it's actually training itself on your preferences and then feeding you back answers you like and thinking about the implications for ‘How we know what we know’ when an algorithm is designed to make us happy as opposed to giving us the truth or whatever that might look like. So I think we've had some really cool lessons of thinking about math and algorithms and how ChatGPT and generative AI in general can influence ‘How we know what we know’ and how we need to be skeptical of the information we're consuming for that very reason.”

“I find it really helpful as a tool to review,” said student Henry (Junior). “In my history class, we get a blue sheet with all of the class content for a unit, and I can feed that into AI and it'll quiz me on all the class topics and help me better understand what I need to touch up on before a test or a debate. So I think that's a really good use for it.”

Ninth-grader Jillian also finds Gen AI highly useful in her math studies. “In my math class, I like to use it [when] I don't know how to answer a problem, I'll have it explain it to me. And if I'm still confused, it can usually go about explaining it in a different way, which is very helpful. I also will have it give me similar questions that I can still practice so I can feel more confident on a test.”

TOK teacher Healy has also found constructive and creative uses for AI in the classroom. “Theory of Knowledge introduces students to different experts in the areas of study. And so, for one assignment, for example, I had students 'interview' that expert. So they had generative AI pose as that thinker, and ask it questions, which was really interesting for them. Personally, I've [also] used it when I wanted to adapt something. So, I had written a lesson plan for a Contemporary Ethics course a couple of years ago on social contract theory, and I wanted to adapt it actually in the IB Business realm when we were looking at organizational structures and corporate social responsibilities. So I said, ‘Help me adapt this. What would you do?’ And that was just a fun exercise to see what it would turn out and then take what it gave me and then build out my lesson further.”

“One of the most helpful ways I've seen it used and that I use myself, is to give it, my work for a summative assessment and give it the rubric for that assessment and have it assess it as if it were a teacher grading it on that rubric so I can see where my strong areas are and where areas I need to improve are,” said Senior and Student Representative to the Falls Church City School Board, Aiden Harper.

Computer Science teacher William Snyder also finds Gen AI a useful educational tool for teaching coding. “One of the areas I've used it is in the Computer Science class.... Students could put their code in to figure out where their errors are, to find syntax or semantical errors so that they’re not spending too long struggling inside of a problem. And it will also help them become a better programmer.”

Academic Integrity and Gen AI Limitations for Students and Teachers

“What have you noticed about the limitations of Gen AI?,” asked moderator Singer. "Are there times when you’re thinking, 'I need to be the human in this process rather than just working with the machine'”?

In response, each panelist was quick to highlight problems with Gen AI for teaching and learning.

“Mr. Peet mentioned this before, but it always really likes to tell you what you want to hear," said student Henry (Senior). So you have to kind of be a moderator in that process and know when you’re actually getting something that's useful to you, and when you're just getting some feedback that’s there to make you feel good and keep using it, because its goal in the end [is] to get you hooked and get you to be a longtime user."

Though he uses Gen AI cautiously in class, Computer Science instructor Snyder finds the application to be “not very good at math” and certain aspects of coding. When he taught math, he demonstrated its math calculating limitations to students. “It’s actually a little troublesome with coding too – you have to fact check it – and that becomes a point in talking with students that we can't assume everything coming out of it is accurate."

Teacher Healy has run up against students not having up-graded and pricey Gen AI accounts that will let them process longer texts. “I actually had an experience yesterday where I gave a class a reading and then we were going to have a reading quiz on Friday and I told them, ‘You know, you can use the AI to help you once you’ve read, to come up with some study questions. And they were like ‘24 pages of reading!’ So, some of them scanned the reading and, because it was too big, they had sort of used up – if I understand this correctly – their limit on what they could upload.”

Students also had difficulty developing their own study guides using AI. After some prompted the chatbot with topic areas, “AI came back with questions that weren't relevant to what I had asked them to read,” Healy said. In the end, the students “ended up creating a little bit more work” for themselves than they might have by generating their own study tools.

Senior Aiden Harper also warned of the inaccuracies of Gen AI content. “As Henry said, these AI machines are black boxes making educated guesses about each individual word. It’s just thinking, ‘What does the user want to hear? What will make the user happiest with how the machine is performing?” Since the machine “has the ability to just completely make up information, from no reputable basis,” users must be sure to fact-check.

Cases of Cheating?

Ella (Junior) claimed to have seen AI used to violate academic integrity. And she has not always been impressed with the quality of its output. “I’ve seen a lot of people use it in English class to like, if you just have a little paragraph due or something, and you're just like, ‘Why would I spend 30 minutes on this when I can just have AI create it?,’ she said. “But, it gives a lot of people similar answers to each other, so you can tell in that way. And then, the answers are just very bland, and it just sounds like you kind of reworded the prompt sometimes instead of actually thinking of an answer.”

Jillian (9th grade) said her English class had just finished reading Frankenstein and the class was assigned to write paragraphs and quote responses. However, she claimed, there were “a lot of students who did not read the book and still used AI and I think they got better grades than me.” She added that teachers “need to be aware of when students are and are not using AI.” When teachers use AI checkers to try to spot cheating, she said, “AI checkers are obviously not foolproof, but there are other ways to figure it out."

TOK teacher Peet described the situation in schools as “the Wild West of AI right now.” But, he argued, it’s likely to improve over time. “This is the worst AI is ever going to be, right?” he said. “So, every time we acknowledge a limit of AI, we come back to have the same conversation…. So, to Jillian’s point, teachers are spending a lot of time thinking about how do we change our assessment practices, right?.... How do we update how we hold kids accountable for learning the information?” But, while updating assessment practices, teachers will also need to “teach kids to ethically and responsibly use generative AI, because it’s not going away.”

Are the Students Losing Trust in Themselves?

Teacher Healy poignantly remarked that something’s being lost as students turn more and more to AI tools. “So often I’ll see students jump to it very quickly to answer those questions. And my concern is they don't trust themselves enough. They really are good thinkers. We have created good critical thinkers in this school, and some of them will, and maybe just [due to time pressures] [use] it when actually they don't trust themselves enough. But I wish they did because they're really bright, engaging students who have a lot of really good ideas. And I think that's what sort of breaks my heart about this. It's a fantastic tool, but, in moderation. And I also worry about the stamina for things like the readings I give. I worry about their stamina for deep critical reading.”

Misconceptions Surrounding Gen AI in School

Moderator Singer wanted to know what misconceptions panelists believe “might exist around AI in our school?”

Ella (Junior) said too many teachers view student use of Gen AI in black-and-white terms – either they use it completely or they don’t use it at all. “But, students like to use it in all different ways,” she said. “Some do actually give it a prompt and [then] copy and paste it. Some just ask it to make an outline. Some will modify it enough that it really does sound like they wrote it. So, you can't really just say ‘You used AI or you didn't.’ And it's really hard to actually draw the line in between. Or, students will think just because they didn't go all the way by copying and pasting, that means they shouldn't get in trouble for it.”

For Senior Aiden Harper, there are huge gaps in understanding how AI is used across just about every interested group. “I think that one of the biggest issues with generative AI and just the understanding of it, amongst the teacher, student, and parent populations [is that] there's just a complete disconnect in the understanding of how it's being used.... I've had different interpretations of how we're able to use AI from different teachers across different subjects, and even within the same subjects.... They have different things they're okay with and different things they're not okay with. And the same level with students, as was said earlier. Students use it in a lot of different ways, which is one of the big contributing factors to this. Some people obviously use it in a bad way, but other people don't use it in a bad way. Some people use it in a way that's not going to make them not able to do the work, and they don't use it just to copy and paste. They actually use it to enhance their understanding, to make sure they’re doing well in their work and they’re properly learning. So, as a school and as a school system, we have to make sure we’re bridging these disconnects and improving the understanding of all of our populations.”

Teachers Using AI for Grading

Ninth-grader Jillian also highlighted her concern that many parents don’t realize how much teachers are using Gen AI for grading students’ work. While she finds the use of Class Companion, a school-approved Gen AI tool, helpful and “very beneficial” to her “understanding” in her English and History classes, she said some students use ChatGPT appropriately while others do not, and “trying to draw a line” about “what is acceptable” is “extremely difficult.”

Recalling the “Wild West of AI” theme, TOK teacher Peet pointed out that many workplaces are also currently divided over the proper use of Gen AI for applications and work functions. So, “How do we use it?," he asked. "Kids are trying to figure it out. Teachers are trying to figure it out.... We haven't gotten all on the same page because many teachers have different comfort levels with technology, different knowledge levels, and we're trying to level the playing field right now. And I think.... we're gonna get closer to that.”

“I’m still figuring out AI,” teacher Healy said with a smile. “I learn a lot from the students who show me how they use it and how it works and what it can do because I'm not aware of those things. And you know, Peter [Principal Laub] spoke to the launch of Google. And I've used this example with students – this reminds me of the launch of Wikipedia [when] there was all of this hue and cry about, ‘Oh my gosh! …. Students are using that as a source and .... you can't trust it'….. And I think it's something like Jared said, it'll get better over time. We just need to figure out how to use it.”

Senior student Henry also worries about the environmental impacts surrounding the rise of Gen AI, given the rapidly increasing demand for electricity and ever-larger data centers fueled by the AI “arms race.” Though Gen AI provides a “useful starting point” for users, “there’s a lot of environmental cost to that,” he said, adding, “and that is something I’ve looked into.”

What Should Humans Still Be Doing in School?

Moderator Singer asked panelists to consider “What would you like us as a school to still prioritize humans doing?”

Senior Aiden Harper voiced strong concern that teachers should continue to provide a human element to their grading and lesson planning. “As a student being taught by these teachers, a lot of times I can tell when they've created a lesson using AI and when they're doing things like grading using AI, and that makes the education I receive feel less personal and less accurate to what I'm actually doing. So I feel there's still this level of human connection between the student and the teacher that’s completely necessary for learning to happen and that cannot be replaced by an AI”

Ninth-grader Jillian believes AI should not be used in English and History classes for “text analysis and critical thinking,” because “those are skills that need to be learned,” by students doing the work themselves.

Junior student Ella would like to see more interactive class discussions to incentivize reading and understanding. She has seen students more prone to copy and paste when they’ve only been asked to summarize a piece of text. But, when she has group annotations in her TOK class, the opportunity to “talk about it with other people at the same time,” facilitates the deeper learning and communications skill-building.

Reading Stamina

Aiden Harper (Senior) shared insights into why students are having less and less reading stamina for longer passages. “Ella raises a good point about reading and it reminded me of how my generation really has started to struggle with attention spans and being able to spend a lot of time on one specific thing, especially reading, because of the prevalence of short-form content applications where the whole premise is dopamine hit after dopamine hit after dopamine hit. It's really decreased our attention span and our ability to read things with a critical-thinking lens. And ChatGPT and generative AI are also contributing to this by giving us this shortcut where we can say, ‘Here's what I have to read. Summarize it in 10 bullet points,” where it's detracting from our ability to get details and get information out of these sources.”

TOK teacher Peet warned that with a renewed emphasis on workplace and vocational preparation and the use of Gen AI tools there’s a risk of losing out on traditional humanities “Life of the Mind” values. For history and social studies teachers trying to teach students how to become “good citizens,” this makes the job increasingly difficult. “If you go to any history education program, it's about citizenship education. How do we prepare students to be citizens in our communities? And that requires critical thinking, background knowledge, and analytical skills…. But I think what I'm hearing from everyone up here is, if we don't have that foundational knowledge, if the ability to read and think critically, to know deeply what our subjects are, [then] the technology is going be wasted and misused. And I think we've got to keep our eyes on the prize there, the big picture, right?"

Where’s the Sweet Spot?

Moderator Singer asked if panelists could describe where their “sweet spots” would be between eliminating Gen AI entirely and fully-embracing its tools.

Mr. Peet emphasized staying “true to core” teaching principles in the classroom while not being a “complete Luddite” opposed entirely to its use. His guiding question: “What does technology allow me to do in the classroom that I couldn’t do otherwise?” He cited 9th-grader Jillian’s embrace of Class Companion for formative assessments earlier in the discussion as a good example, because the entire class can receive feedback using the application whereas he could only circulate to give in-person over-the-shoulder instruction to maybe five or six students in a class period.

“I think we don’t wanna be stuck in our caves in the Stone Age while the rest of the world is moving on to bronze tools,” Aiden Harper said. Students will need to be prepared for their technological futures, but “we can’t push it so far forward that it becomes something that distracts and detracts from the education the students are receiving.”

Ms. Healy then offered a “sweet spot” anecdote. “I like to think of it too as a teachable moment,” she began. “The other day in one of the business classes, kids were asked to come up with a prototype of a product. We're in the marketing unit and we were talking about market feedback, and niche markets. So they were coming up with prototypes of these new and improved products or something that would be appealing to a niche market. And one group was trying to do a toothbrush that also dispensed the toothpaste. And so they used generative AI to come up with an image for their slide... and it came up with something that you would never put in your mouth.” [Laughs].

“But what we played with was how to ask the question so it could come up with something,” Healy continued. “And that was a really fun endeavor and just a way to think about how do you ask a question? How do you describe what you want? What kind of language should you be using? And so, in that instance, it was really a fun thing to play with and a way to incorporate it, but to also still use critical-thinking skills and imagination.”

Audience Question Sparks Intense Discussion

After Moderator Singer opened the floor to parent/guardian questions, some criticisms of current teacher practices with Gen AI surfaced.

“We met a senior a week or so ago who was disconcerted and upset that her research paper was graded by AI and the comments and the grade apparently were entirely determined by AI and I was wondering if there’s a policy on that at the school ... and what the school thinks of that?,” an anonymous audience member in the front row asked.

Singer quickly stepped in to protect the panel from having to answer the question directly and to re-frame the discussion a bit. “So, I don't know that I can kick that one to our panel, but I might pivot it and give to our panel an opportunity to say what their perspective on that would be. So teachers and students, from your lens, what is the role of AI when it comes to assessing student work?,” he asked tactfully.

Soon, student panelists jumped on the complaint.

Junior student Ella would like more than basic AI feedback on how her work might or might not fulfill basic rubric requirements from the teacher. “I’ll get feedback and it’ll just be like, ‘You did a good job doing this,’ and it’ll just restate what the rubric says. But, if a teacher were grading it, she’d be able to tell me how I can actually make it even better and specific to her class.” Ella also expressed concern that summative assessments are graded by the teacher directly, so “the AI won’t catch something that I should have done on the summative, because it doesn’t know.”

Senior Aiden Harper then unleashed the floodgates. “I can corroborate that. It is frustrating when we have these bigger assignments and we're expecting helpful feedback, especially because we put so much time and effort and energy into presenting these massive bodies of work. It is very frustrating when we go to see how we did and how we could improve. And it's just like slop from a generative AI and there's nothing helpful and it's just restatements of the rubric.”

Senior student Henry then said with levity, “I mean, like if I wanted AI feedback, I could probably go get it.” [Audience laughs]. “And, that’s kind of the whole thing, like that kind of connection with the teacher and being able for them to, you know, give their input and how they feel, that you can understand. I feel like that’s a big part ... of the whole learning process and taking that out makes it feel a whole lot less rewarding.”

Teacher Peet then pointed out how difficult it is for teachers to provide individual feedback on every task. “I don't use AI to grade anything, obviously. So it's interesting to hear that, just from the teacher perspective – not to defend that practice in any way – but, it is really hard to provide individualized, detailed feedback to all of your students repeatedly. And so, again, not excusing that, but I think where I've kind of come to fall is a lot of times, students will look at their grade and then turn their head away from the assignment and the feedback doesn't really matter and [it] almost becomes a grade justification. So ... I've really changed my practices in the past couple of years to require students to use the formative feedback to improve their work. And if it's just like a summative assignment, I'll give them a grade…. And I say, if you want to discuss it, please come on in during a Mustang Block. I'm more than happy to do that. And very few students do.”

But then, Mr. Peet pivoted to express empathy for the students who feel short-changed by having their work graded by Gen AI. “I share the students' frustration because it's not great to hear you guys have had that experience.” He added that for both teachers and students “there’s a human element to this” and the “temptations” to save time are “hard to resist sometimes.”

Moderator Singer drew the discussion thoughtfully to a close by highlighting the faculty’s fall reading of the book Never Enough, which stresses how a student’s sense of “mattering” in the school community helps “lead to better esteem and better outcomes.” So, he suggested that teachers remind themselves that “No, this isn’t the 50th paper I have to grade, but it’s Aiden’s paper, and I know he was really excited about this idea in this paper.”

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion