Viet Place Collective’s Activism Key to Falls Church City’s 2024 VML Innovation Award

Democracies function best when community-minded citizens are encouraged to pressure local governments to listen to their concerns.

The story of the Viet Place Collective (VPC), an advocacy organization representing the City of Falls Church’s most expansive commercial zone and the City's number-one tourist attraction – the Eden Center – provides an inspiring example of the many positive effects such community-minded movements can yield.

Fortunately for the City of Falls Church, the willingness of its leaders and government officials to dramatically change course in its commercial zone planning process and listen to the Viet Place Collective’s call for better citizen outreach has not only brought a positive change to the City’s approaches for Falls Church City’s’ East End, but garnered high-level state recognition for how local governments ought to function.

In her Oct. 25 weekly newsletter, City of Falls Church Mayor Letty Hardi expressed rightful pride in the City’s reception of the 2024 Virginia Municipal League’s Innovation Award for Communications for the City’s East End Small Area Plan (SAP) which provides a “vision for reinvestment” in the City’s eastern commercial zone, an area encompassing the massive Eden Center – the largest collection of Vietnamese shops and restaurants on the East Coast with over 120 businesses.

“The theme of outreach has been top of mind for me,” Mayor Hardi wrote. “Besides writing these weekly-ish posts – as our city grows, it requires more deliberate effort to listen to a cross-section of perspectives.”

Though the mayor played a key role – stretching back to her days as the City’s Vice Mayor – in urging better communications between the City’s Planning Office and the Eden Center’s many Vietnamese-speaking business owners, the concerted voice of those business owners could not have been heard without a handful of highly effective and determined citizen activists from the Viet Place Collective.

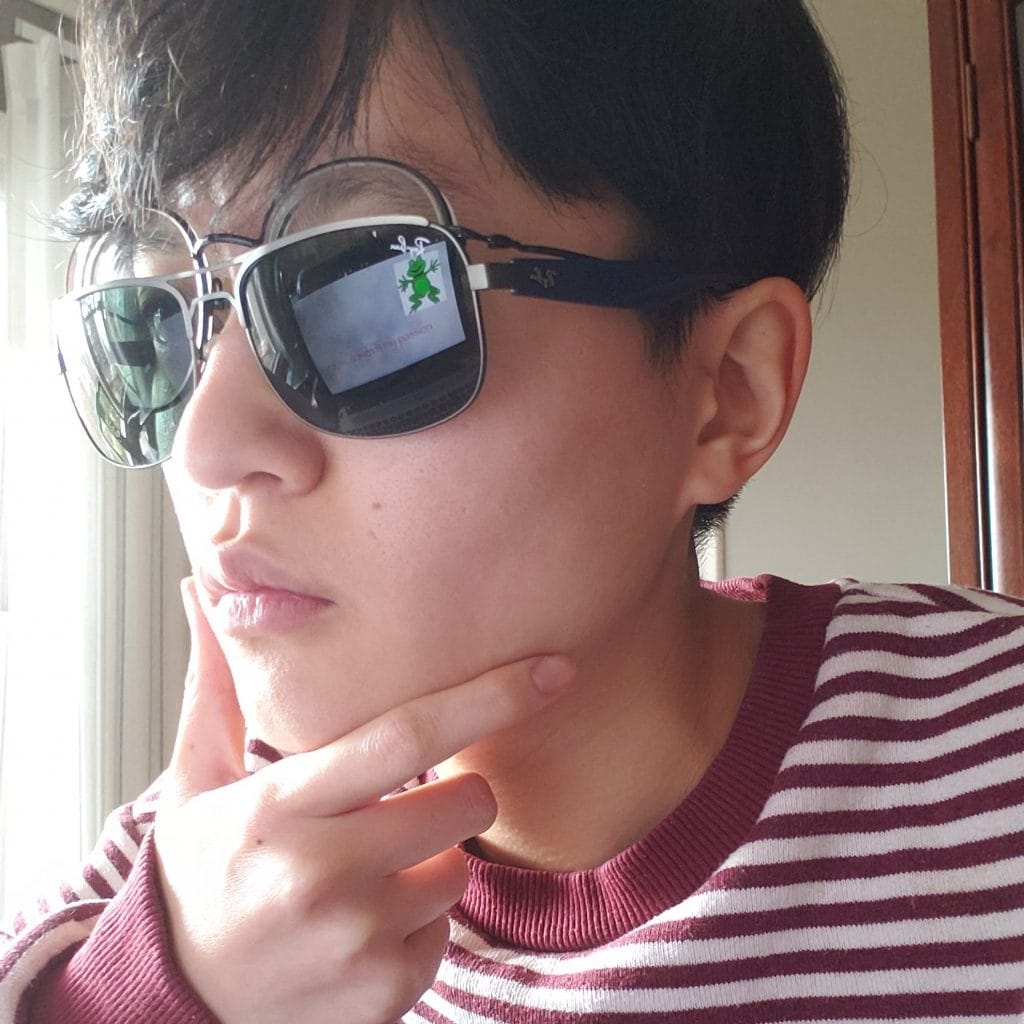

Interviews with VPC Founders and Core Organizers

For this article, The Falls Church Independent interviewed two of the Viet Place Collective’s founders and core organizers, Binh Ly, a 33-year-old city planner, and Quynh Nguyen (they/them), a 26 year-old digital communications coordinator for the local nonprofit Hamkae Center.

We wanted to learn more about how a small batch of determined local activists could apply such effective political pressure on local government that they could persuade it to hold many more community outreach meetings than originally scheduled and to alter so dramatically the City's East End SAP to include so many of the group’s demands for the Eden Center's Vietnamese cultural preservation.

I asked Binh and Quynh to describe their backgrounds and what inspired their activism. While they have friends and family members who are business owners at Eden Center, neither has a direct business interest in their cause. “I was born and raised in northern Virginia. Went [to the Eden Center] throughout my life, still do, with family and friends…. And I studied Urban Planning in grad school at Virginia Tech. And actually, Quynh was the one who looped me in when they were going to start this Small Area Plan. So, I’ll take it over to you, Quynh,” said Binh.

Quynh teased Binh. “Binh fails to mention that he took part in an oral history project documenting the history of Little Saigon Clarendon during his grad school years," they said. The two had met in the Urban Studies Department at Virginia Tech where Quynh did their undergraduate work and Binh worked on his Master's degree. "He put me on to local Vietnamese history which I did not know about, despite growing up in the northern Virginia area my whole life. I still live here. I live with my family. We don’t live in Falls Church. We live a little west of that in Vienna. But I also have grown up going to Eden, engaging in a lot of Vietnamese cultural activities. So being in this area has helped me appreciate being Vietnamese.”

Embracing Anti-Displacement, Anti-Gentrification Strategies

The story of Vietnamese business displacement from Little Saigon in Clarendon and the urgent need to prevent such dissolution from the Eden Center inspired Quynh and Binh to educate others on anti-displacement and anti-gentrification strategies in the Vietnamese cultural hub they grew up cherishing in Falls Church. “So, in Clarendon today, there’s only one Vietnamese restaurant left [from the original Little Saigon] and it’s called Nam Viet. And it’s there because they own their land. So, they’ve been able to hold on. But the renters [of other Vietnamese businesses] are no longer there,” Binh said.

“When I learned about this local history of Vietnamese people being displaced from Clarendon to Falls Church – and that’s what created Eden Center – it helped me better understand the situation my community has been facing,” Quynh said. “And when we heard those plans about the Falls Church East End Small Area Plan – they had started in November 2021 with the stakeholder meetings and such and then did a community meeting... and we [only] heard about it through a news article. A small group of Asian Americans, many Vietnamese Americans, in about January, 2022, started collecting information about the plan. That’s when I looped Binh in, because he has a deep knowledge, having been involved in the Vietnamese community in this area for different organizations for a long time.”

Rising Rents Fuel Displacement

So, what led to the displacement of the restaurants and businesses that made up Arlington’s vibrant Little Saigon in Clarendon – so active in the late 1970s and early 1980s?

“So, the area around Clarendon was depressed before the construction of the [Clarendon Metro Station] in the mid-70s, so there was vacancy and very cheap rent, I think in the single digits per square-foot,” Binh said. “So the Vietnamese businesses were there through the opening of the Metro. But with the opening of the Metro [in 1979], as you can imagine, rents started to increase, and Arlington County went through their own planning process to encourage development. There are clippings of these news articles that say, ‘Oh, we will preserve these storefronts.’ And they did, right? The storefronts are there. It’s just the contents of the storefronts are no longer there.”

Avoiding Caricature

But ongoing cultural and business displacement today in Chinatown DC also serves as an object lesson, another compelling argument VPC can muster to rally Eden Center’s business owners to make their voices heard in the City of Falls Church before it's too late.

“So I think that’s something that made our advocacy successful, that it’s not only this example of our own community being displaced, but just down the street and in Chinatown in D.C., we could see they pay a lot of lip service to cultural preservation, right? To preserving the look and the language. But now you have Chipotle with Chinese characters, or Starbucks with Chinese characters and there’s hardly anyone Chinese left. So it’s a caricature of itself, right? And that’s what we wanted to avoid. So we have all these very, very clear examples of what could happen.... The Plan as it existed before we got involved in Falls Church City only paid lip service to preserving the culture. You would read through the Plan and there weren’t any concrete strategies for preserving the businesses there or the people or the community there that makes it what it is.”

Activists Become a Collective

Before Quynh, Binh and other concerned Eden Center supporters named themselves the Viet Place Collective, they were simply an online chat group for anti-displacement and business/landlord concerns. “Well, it started as a group chat. We didn’t actually name ourselves until December 2022.... We did a lot of research ourselves to understand the City process, like, 'Why are they doing the Small Area Plan in the first place?,' 'How will it affect Eden?,' and doing outreach to those small businesses at Eden to ask if they know about these plans, to ask our community really broadly if they know about the consequences of development and what it has historically done to communities of color that have made a place vibrant.”

Selecting a Name

Binh explained why they chose to call themselves a “collective.” We chose “Collective,” and I think it’s what made our advocacy successful… [the concept] is that we are from a diverse background, and diverse skill sets. A lot of us work in the public sector but we have folks who are working in nonprofits as organizers, as creative folks, musicians, artists, and I think that really embodies who we are, because we don’t necessarily agree on everything. But we’re here with a common purpose, right? The reason why we say “Viet Place” – it’s generic but also meaningful.”

Tenant/Landlord Issues

While Quynh and Binh emphasize the need to maintain a "working" and “diplomatic” relationship with the Eden Center’s landlord – Capital Commercial Properties, out of Boca Raton, Florida – they’re also candid about the tensions between the Eden Center's owner and the many small restaurateurs and business owners that make up the vibrant Vietnamese community licensed to do business there. “You know, our community doesn’t necessarily have the best relationship with the landlord. I think it’s a very exploitative relationship at the Eden Center,” Binh said.

“I don’t know if you know, the name “Eden” is named after the Eden Arcade in Saigon and it was formed by a group of Vietnamese business people after having left Clarendon, but they sold the name,” Binh continued. “So now the ownership is no longer within the community. So... yeah, there’s a working relationship with the landlord, but it’s [only] one landlord for over 100 businesses. So oftentimes there’s a divide and conquer mentality with these businesses. So for us it’s an uphill battle, trying to stitch our community back together.”

What Makes the Eden Center Worth the Battle

Binh explains what makes the Eden Center worth battling over. “Our goal is to fight for this place that’s not just for small business activity, it’s much more than that. These small businesses are the crux of our community. You know, we celebrate the fall of our parents’ nation [South Vietnam] in the parking lot, unfortunately, right? [Laughs]. Because we don’t have a better gathering place. We celebrate our New Year in the parking lot of the place. So, for us, this is a beginning point, advocating for these businesses. But we also feel like our community deserves recognition for all we’ve contributed back to this area. And also, we deserve a place to feel dignified and not feel displaced.”

“These are all small businesses,” Quynh emphasized. “There are very few chains in the Eden Center…. There’s a lot more to the Eden Center than just food. There are small businesses there. You can get your taxes done. There’s job development. You can talk to your parents and give them credit and ship them money. You can get your hair done… It’s not just food that brings people back, but these necessary services and salons and other kinds of stores. For a lot of people it’s a one-stop shop…. So we’re advocating for the City to invest in these small businesses, not just in the Eden Center, but around the City to make sure they can stay.”

For Quynh, the Eden Center is “something like a treasure definitely to the Vietnamese community, to the Southeast Asian community and the Asian-American community. And I know the residents of Falls Church City and the surrounding NoVA area also recognize it for the intrinsic cultural value it brings.”

Such concern should also extend to Ecuadorian, Salvadorian and other ethnic businesses, Quynh argues. Small business grants could be used, for example, to “make sure owners can equitably access resources and information [to] make sure we’re on a level playing field with other White-owned small businesses in the area." Providing technical assistance, and pro bono legal support would also be effective.

Origin Story of VPC

The City’s Planning Office officially launched the East End SAP in November 2021, but the Viet Place Collective didn’t officially launch until the following year. Many were unaware the City was even contemplating “reinvesting” in the East End commercial area, many were afraid it meant “redeveloping,” – i.e., ejecting businesses and bringing in the bulldozers – and many within the Eden Center community were unaware of any outreach efforts by the City about "the Plan."

“We formed around the end of 2022 officially,” Binh recalled. “But Quynh and a few volunteers had been reaching out to the City throughout 2022 to see whether the City had reached out to these businesses to get their feedback…. There was [only] a staffer who went around and handed out flyers to a community meeting, right?.... So, I think the biggest lesson we’ve learned and that we’ve taken from the process is that what’s legally required is not sufficient.”

Following online pressure from Viet Place Collective’s impressive social media operations, the City agreed to slow down the planning process around the Eden Center and to boost its community outreach and allow more voices to be heard from the Vietnamese business community. “The second community meeting was supposed to be in March 2022 and they moved it to November…. And they wanted to approve the plan by March 2023,” Quynh recalled.”

How to Do Outreach

“So, one year after they had started the Plan, we asked them, ‘Did you do the outreach?,’ ‘Did you include the community at the center of this Plan?’ And they only said, ‘We translated flyers and we’re holding ‘community meetings’ [Air Quotes]. Like these community meetings are often at the church that’s right next to the City Hall,” Quynh continued, emphasizing that many Vietnamese business owners felt excluded not only by the process but by the selected venue of an unfamiliar church.

“So, in November, I believe they had a meeting at the church, right?,” Binh asked. “And we had organized community members and tried to get business owners and, I think, one business owner came out –” Quynh corrected him and interjected, “Two.” Binh acknowledged and replied, “Okay, two.” With a laugh, Quynh contextualized: “I was the one who did that outreach actually."

"I kept asking the planners, ‘Did you guys go to the Eden Center?,’ ‘Did you guys talk to any of the businesses?’ And they didn’t," Quynh said. "So we gave up. I stopped relying on them. I was, like, ‘Nevermind. You print out flyers in English and Vietnamese, and I will do that outreach for you.’ Because, before we were called VPC, we were really adamant in ensuring that community has a seat at this table. That our concerns are heard. And the fact that the planners did not do any outreach prior really did not sit right with us.”

“Prior to our involvement, the relationship between this community of businesses and the City was just speaking directly to the landlord, right?,” Binh said. “And that counted as ‘They did their outreach.’ But for us, we’re trying to remind the community, the City, everyone – even our own community – of the importance of these businesses to our community and why we need to speak up. Because at the end of the day, the shopping center would not be what it is, would not be a regional attraction, if it weren’t for the small businesses that keep the culture, the food, the smells, going, right? That attract people to this area and this part of Falls Church.”

Until the VPC involved itself in the community outreach process, City planners didn’t appear to take demographic factors into account. “The staff themselves were White. None of them was Vietnamese,” Quynh recalled. “So there’s that language barrier that could be fixed with a translator if they cared to do that outreach, but we mobilized a bunch of Vietnamese people to come to that second community meeting where we told them, ‘You’ve got to do more outreach to the Vietnamese community.'"

The City Starts to Listen

Fortunately, the City was responsive to VPC’s calls for improved community outreach.

“And they heard us,” Quynh said. “And they scheduled an extra community listening session in January 2023 and we named ourselves VPC then and we mobilized over 70 people. We gave over 30 public comments at the City Hall. I think one of the planning commissioners said, ‘This is, like, only the second time [I've] seen City Hall this packed.’

“And [at the City Hall community meeting], we expressed the same concerns about the lack of outreach to Vietnamese people and then we had things to ask of them,” Quynh recalled. “For example, first, you need a Vietnamese Outreach Specialist to build and maintain the relationship between these businesses and the City. These businesses often have a lack of trust in the City. Generally, City processes are hard to understand, even for people who grew up in the U.S. like me. As I was doing it, I had to learn how planning processes worked and how the City processes worked. And that might be even more daunting for a business owner who might have limited English proficiency, who might be a recent immigrant, or simply doesn’t have the time to go to City Hall to make their concerns heard.”

A Sympathetic Vice Mayor, Turned Mayor

Given that Mayor Letty Hardi is Chinese-American, wasn’t she more sympathetic to your cause, I asked. “Yeah, Letty Hardi was then the Vice Mayor. She supported our ask to have a Vietnamese Outreach Specialist, Quynh said. “She expressed wanting to support more tenant protections as well. We’ll see how that plays out, or, how do you say, turns into policy in the future. At least for the Vietnamese Outreach Specialist, we were successful in that ask. They have allocated, I want to say 30 grand this fiscal year and the next fiscal year – fiscal year 2025 and fiscal year 2026 – to have a Vietnamese Outreach Specialist. But, we’re [now] in fiscal year 2025, I think, and they still haven’t posted the job description.”

“I think the current mayor – which at the time [she] was not – she also comes from a background of small business owners, right?,” added Binh, who agreed that Mayor Hardi was supportive.

To the City’s credit as well, one member of the City’s Planning Commission was an expert in anti-displacement studies and helped spur both the City Council and the Planning Staff to revise their approaches to community outreach. “I think throughout the process we were interfacing a lot with the Planning Commission as well,” Binh recalled. “And I think our biggest advocate on the Planning Commission was Mr. Derek Hyra who’s a professor at American University. And because this is a planning process, it goes through the Planning Commission first, and then the City Council does the final approval. So we had the January meeting and then the process was further delayed and they agreed to do four pop-ups at the Eden Center, in person.”

So, hand-in-hand, Professor Hyra's impact from within the Planning Commission and the VPC’s community activism was huge. "They hadn’t done any pop-up meetings [designed to elicit direct public input and feedback] at the Eden Center before. They had never actually come to the small area and done a meeting there,” Quynh said. “We usually just do community meetings.”

City planners didn't seem to take into account the challenges small business owners faced in providing the City with critical input. “I mean they had staff come and hand out flyers, right? But for us, what we tried to communicate to the City and to City planners was that these are small business owners who are working more than eight-hour days and we can’t expect them, after work, to go up to share their wishes for the future when a lot of them are just trying to put food on the table just for today,” Binh said. “They don’t have the resources to be thinking about what could be [done at the Eden Center].... So, trying to get the City to understand that these are working people who need more support, whether it’s technical assistance or language support.”

Soon the VPC’s painstaking activism began to pay off. When the vote to approve the final draft of the East End SAP came before the City Council by June of 2023, several of VPC’s demands were included in the final language of the City’s official plan for its most tax-lucrative commercial district.

“So the City voted on the Plan and we were able to work with the Small Business Anti-Displacement Network (SBAN). It’s based out of the University of Maryland,” Binh recalled. “And we incorporated a lot of their Anti-displacement Toolkit, which are strategies for anti-displacement. So we offered that to the City as edits to the Small Area Plan. We still have the red markup of the plans which show the additions to the Small Area Plan that we advocated for and, the City – a lot of credit to them – incorporated much of it into the Plan.”

On their website, VPC could now translate their successful campaign to alter the City's East End SAP into greater credibility: "Viet Place Collective is an all-volunteer grassroots organization that aims to build power across generations to uplift and uphold the Vietnamese community's legacy in the DMV. VPC formed in Dec. 2022 in response to a redevelopment plan by the City of Falls Church over concerns about displacement of the majority-Vietnamese small businesses of Eden Center, the largest Vietnamese cultural and commercial hub on the East Coast and the cornerstone of our community in the region. We’ve championed the importance of preserving a cultural hub, recognizing the Vietnamese community's history of displacement as part of a greater trend of gentrification nationally. Within just a year, VPC's advocacy has improved conditions at Eden Center, brought Vietnamese voices and an anti-displacement toolkit to the City’s plan, and raised the City's standard for equitable outreach to impacted populations."

The City Council's adopted version of the East End SAP includes many suggestions demanded by the VPC: anti-displacement demands, naming the area Little Saigon, displaying bilingual banners, honorarily renaming a portion of Wilson Blvd. "Saigon Boulevard," public art enhancements, addressing parking concerns, traffic safety, and enhancing events spaces. But, no legal guarantees could be made for such VPC's suggestions as establishing "legacy business grants," a "special tax district" to help fund business grants, a "neighborhood business incubator," or "construction disruption mitigation."

Nevertheless, the City's commitment in the Plan to the language of anti-displacement and its re-enforcement of the need to preserve the Eden Center as a hub of Vietnamese culture in the City of Falls Church represents a major community activism victory.

Challenges Ahead

But now comes the real challenge. How can the VPC ensure the City follows through on its commitments? It’s one thing to offer a Plan as a “wishlist” and another altogether to fund it sufficiently to ensure that its vision is truly realized.

“So Planning Commissioner Derek Hyra during the vote said that this was one of the plans with the most equity language of any Small Area Plan in Falls Church City,” Binh said. “So I think that was an incredible victory for the community. But there’s still much work to do. And where we’re at now is we’re advocating to fund a lot of these strategies whether through the City or at the state level.”

“Yeah, the Plan itself doesn’t promise funding,” Quynh said. “That has to be something that is allocated later through the City budget, for example. Or other avenues of funding. But, as Binh said, we got an Anti-displacement Toolkit in the Plan that wasn’t there before. We successfully advocated for the addition of an honorary street name of the strip in front of Wilson Blvd. in front of the Eden Center to be honorarily called 'Saigon Boulevard.' So, no address change. It’s just an honorary thing. But we hope that Saigon Boulevard is kind of a marker to emphasize a larger Cultural District that could be called Little Saigon to put this area of Falls Church on the map with other Little Saigons across the country, like Houston, Texas, or Westminster in the L.A. area in Orange County.”

And how does the landlord feel about renaming Eden Center as Little Saigon East? “He has this reason we don’t agree with,” Quynh said. “He says it will ‘dilute the brand’ [Air Quotes] of Eden Center. But we honestly believe that if there’s an area called Little Saigon, Eden Center will be the center point of it, so the brand of Eden Center will be elevated with this Cultural District. And [the name] Little Saigon is to honor the city that a lot of our parents and Vietnamese immigrants to this area once knew, that fell in 1975 [at the end of the Vietnam War]. So we believe that Little Saigon is a poignant name. Like the South Vietnamese flag flies at Eden and the capital of South Vietnam is Saigon. So we believe that honors the specificity of the Vietnamese community that makes the Eden Center into the vibrant Vietnamese cultural hub that it is today. And it’s also kind of an homage to the unofficial Little Saigon that was in Clarendon as well.”

On the Watch for Economic Threats

Economic development in the region that boosts property values yet doesn't protect small businesses is a major concern. It’s one thing to have good intentions stated in the Plan, but another for local small businesses to handle rising property values and rents as area real estate values continue to increase.

“The strategies are there,” Binh said. “But, once again, they’re only strategies. If no one chooses to implement them, then it’s as good as nothing, right? So I think that’s what continues to drive our work a year on from the Plan passing. Because we are being very preemptive. Development hasn’t started in the area yet. Rents are enormously expensive now at the Eden Center…. It’s about two to three times higher than commercial rent in the area. So there’s already a lot of [business] churn that happens at the Eden Center…. that we have a strong line of communication between the small businesses and public officials when any needs or issues come up, so that our businesses stay vibrant, so that they can stay there.”

Binh cited Fairfax County’s plans to “redevelop Seven Corners” as another factor that could eventually raise rents. “The Ring Road already has funding set aside, so development is just around the corner,” he said.

When asked if VPC promoted rent control policies, Quynh smiled and said, “I wish rent control was a thing. But, unfortunately, Virginia has what’s called Dillon’s Rule which means that if the state law doesn’t allow it, the local jurisdictions [can't] do it.”

The key is protecting small businesses by giving them the tools they need to avoid displacement. “The main thing we want to say is that development is coming but displacement doesn’t have to be an automatic consequence of it,” Quynh said. “If we put in small business protections, if we make sure the City invests in small business preservation – because everybody values small businesses. Everybody loves them. But, it’s kind of like you don’t know what you have until they’re gone.”

“That’s right,” said Binh. “Back to the Chinatown DC example – once that community dispersed, it’s been decades, and there hasn’t been another one, right? Like, you go to Rockville for Chinese food, right? But there’s no congregation anymore. People just got pushed into the suburbs. And that’s what we fear.”

Quynh agreed. “Exactly. There’s development planned in D.C.’s Chinatown and we have friends who are advocating for the low-income Chinese [there]. They’re called Save Chinatown DC. And we’re both sympathetic to each other's efforts. We see that D.C. has prioritized the Chinese look of the buildings, but, when D.C. has prioritized the building rather than the people, that kind of cultural caricature is what results. So, the main thing we brought to the Plan was centering the people and the culture rather than the building. Because if it just says ‘Preserve the Eden Center’ then it could still be called the Eden Center but then one day the landlord might find it more profitable to bring in other [commercial] chains and dilute the Vietnamese identity of Eden. But what we brought was to concretely preserve the Vietnamese cultural identity of the Eden Center and that, for us, is stronger in maintaining the Vietnamese-ness that makes the Eden Center vibrant. Because the property owner doesn’t bring the Vietnamese-ness. The businesses do.”

As VPC has grown and gained influence, it has set its eyes on new and perhaps more demanding challenges. “We started with a handful of us and I think at this point – we’re volunteer run, so people filter in and out, as their availability changes – but I would say we have about two dozen volunteers,” Binh said. “And the corporation that runs the Eden Center I think they’re a private entity – they have representatives in the area – but they’re based out of Florida. And for us, we want to maintain a working relationship with them, but knowing we’re advocating in the small business’s interests.”

“I think we will continue to advocate for the businesses in Falls Church, but it came to our attention that down Route 50 another shopping center, the Graham Shopping Center, in Fairfax County just approved to be developed into a medical center, right?,” Binh said. “And the businesses there – some of them have been there for close to two decades. They were given six months notice to vacate. And it was a mix of Latino and Vietnamese businesses. So we’ll continue to fight.”

“The market is so hot in northern Virginia and rapidly developing,” Binh said. “And so, we want – not just in Falls Church City but local government in general – where policy is being made that the existing rules and regulations do not necessarily take into consideration the immigrant communities, the working class people, that are investing and paying tax dollars that are rejuvenating a lot of these old strip malls from the ‘60s and ‘70s, right? And the public process does not take them into consideration when they’re like, ‘Let’s redevelop and bring in some white collar jobs.’ Well, when you bring in these white collar jobs, you’re causing upheaval within a different community – and then you wonder why there’s homeless people. You know, some folks we talk to have worked at these small businesses, you know, at a grocery or at a nail supply store, they’ve been there for decades.”

“So, I think our job is to illuminate this for the larger public audience and the City,” Binh said. “These are vibrant communities that our tax dollars are contributing to and they aren’t asking for much. We’re asking for a little more. We’re asking for some support. So some logistics and some language support for them.”

“We’re hopeful this will actually lead to conscious, community-centered development, because the plan in-and-of-itself is kind of the first step of development, because after that, and once the City approves [it], then there are zoning changes that have to happen and that’s when developers can come in and ask to develop this parcel of land, for example,” Quynh said. “So, Derek Hyra was talking about how there has to be political will within the City to invest in these businesses to make sure displacement is not a consequence of development. And oftentimes it is, because cities don’t find small businesses as valuable as a high-rise, for example. There’s this intrinsic value of these small businesses, especially in a cultural hub like the Eden Center that has an intrinsic cultural value that you can’t put a number to, whereas they might see the big dollar signs a developer could promise them and that’s what they prioritize. Like increased density and increased tax dollars. Because of course that’s beneficial for the City. But what’s also beneficial for the City is recognizing how important this area is. And we don’t want it to become like a ghost town ... of its past, like Little Saigon in Clarendon."

A Positive Theory of Change

One key to VPC’s success has been their encouragement of the Eden Center business owners to collectivize into their own tenants’ union or business association, rather than urging them to allow the VPC to serve as a governing structure.

The VPC’s outreach and communication model is to obtain maximum feedback from the Eden Center community and use that to shape its activism and policy demands. Getting feedback is “the crux of our work,” Quynh said. “We want to center the people most affected, which are the Vietnamese small businesses. We had done a lot of outreach while the Small Area Plan was being worked on. And then we adapted what we had heard and applied that to the anti-displacement programs that SBAN had laid out in their large Anti-displacement Toolkit. Like, what have we learned from these businesses and how can we translate that into concrete policy to help them with this complaint or concern? And it’s a matter of translating difficult City process info and hard-to-understand anti-displacement [programming] back to the businesses so they understand what we’re advocating for and what the City can do for them.... With the trust we gain from these businesses they become more open to talk to us and we hope this theory of change will lead them to be empowered to speak up to the City or to speak in front of their landlord.”

“We are trying to make sure our community has a seat at the table… If development happens, we will make our voices heard for that…. We fully believe that displacement is not inevitable,” Quynh said. “What it takes is political will and the funding to make those investments in those small businesses.”

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion