Racially Discriminatory Covenants Historically Prevalent Across City of Falls Church

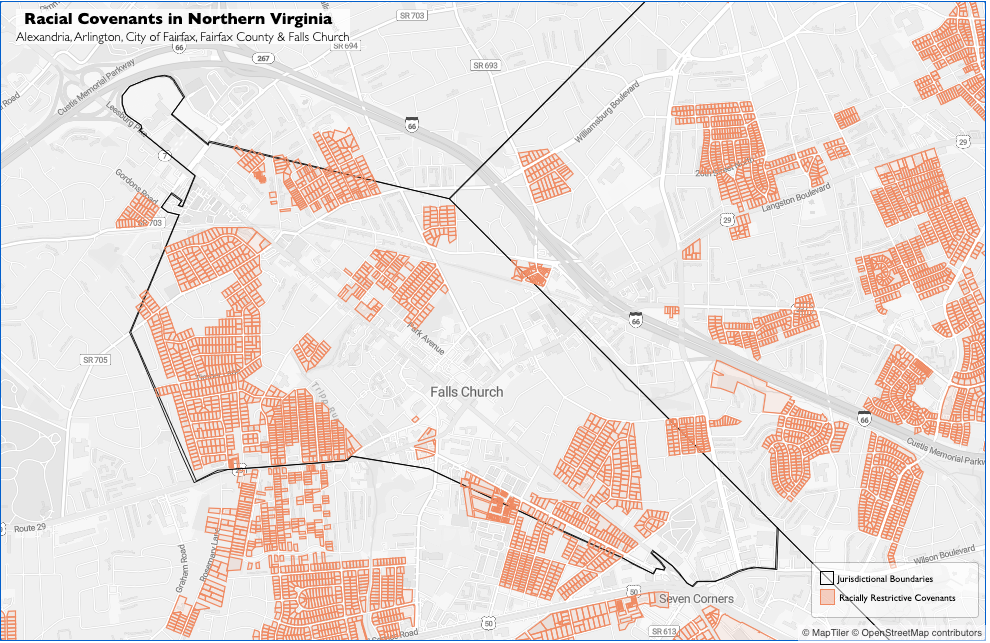

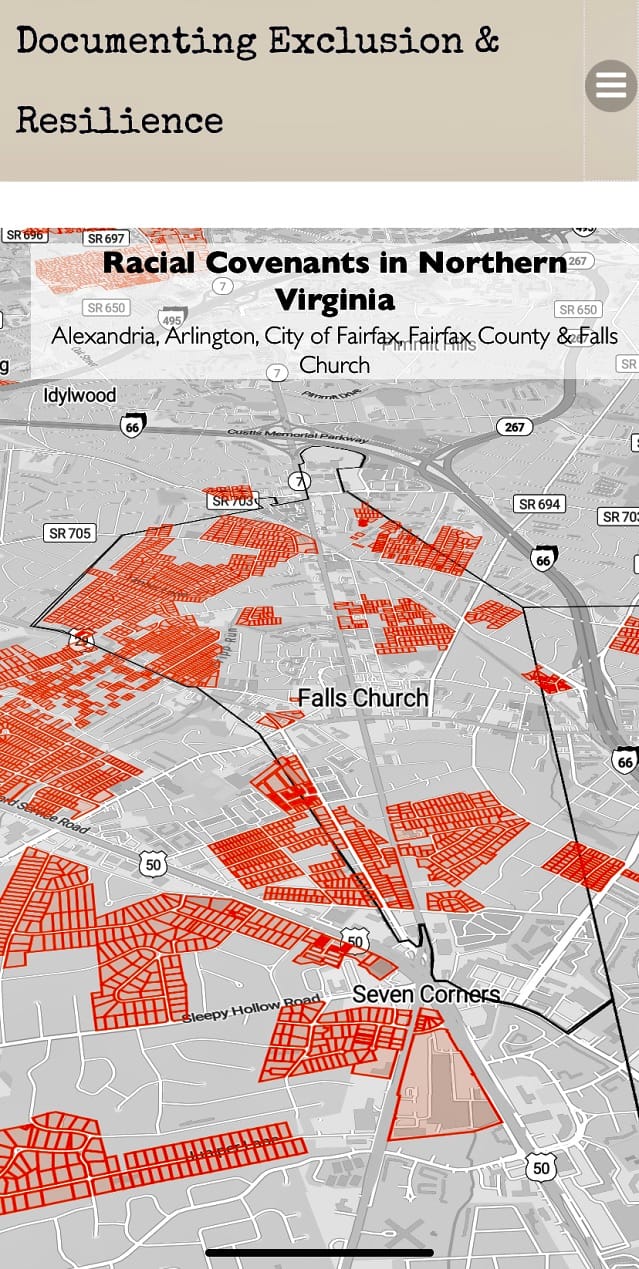

A fresh set of interactive maps from the “Documenting Exclusion & Resilience” project – launched by five professors from the University of Mary Washington and Marymount University – highlight documentary, block-by-block proof of racially restrictive covenants throughout northern Virginia, including The City of Falls Church. Not until the passage of the federal 1968 Fair Housing Act were such exclusionary practices outlawed.

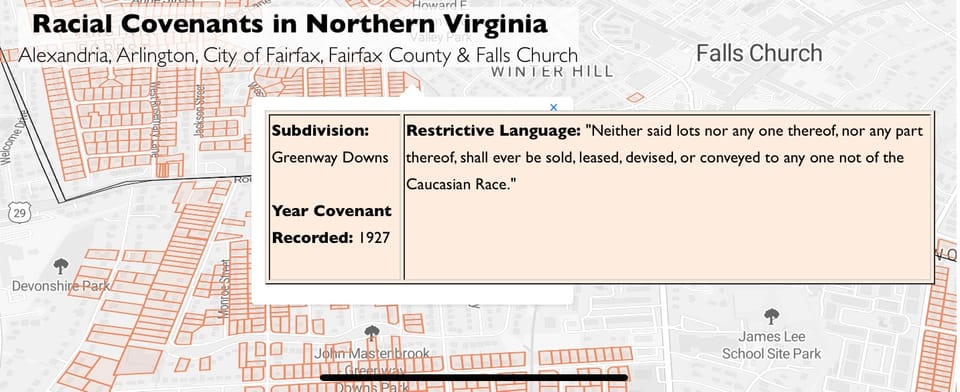

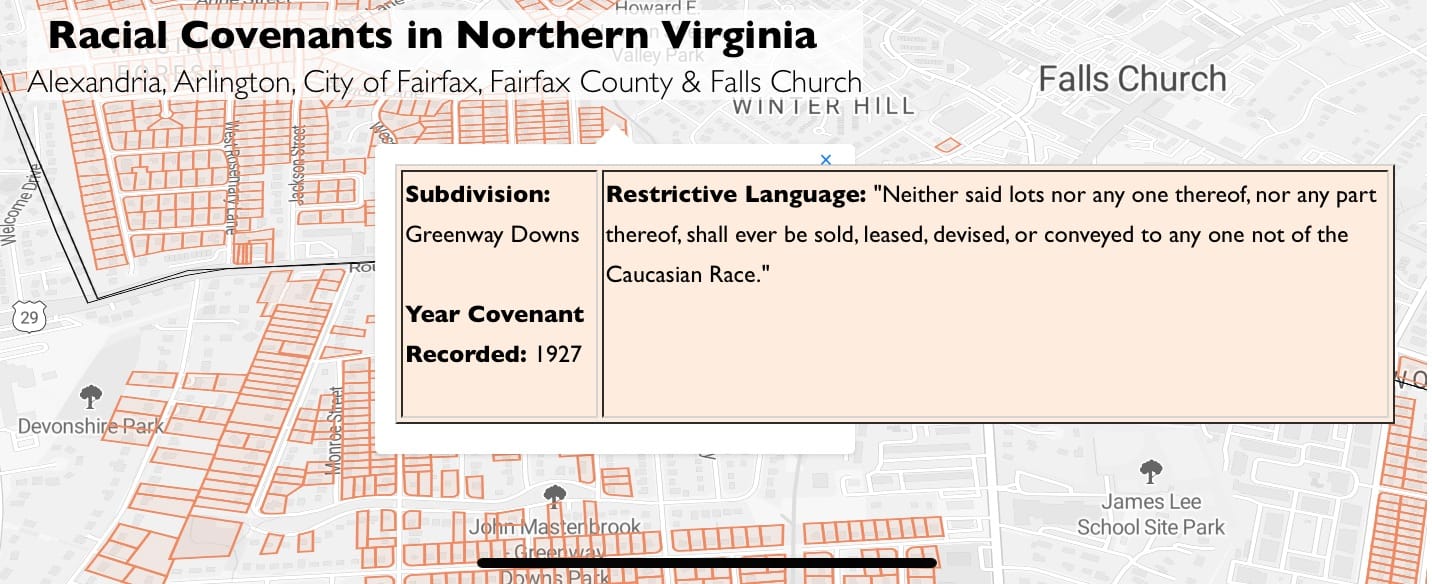

According to the project’s website, the goal of the research is to identify and geo-locate “racially restrictive covenants on properties in Northern Virginia from 1900 through the 1960s,” based on an analysis of public land records.

The socio-economic effects of racial exclusion zones – often barring “any person not of the Caucasian race” from purchasing a property – have been demonstrated by researchers to have negatively impacted inter-generational wealth accumulation, school funding and quality, health outcomes, crime rates, substandard policing, and a host of other variables. Predictably, such pernicious historical effects continue to disadvantage many marginalized non-White groups today.

With the 2017 publication of Richard Rothstein’s best-selling The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, many have become familiar with the term “redlining” – where banks and federal home-loaning and insuring agencies explicitly red-shaded black neighborhoods on maps to exclude them from services to preference the development of all-White neighborhoods.

Rothstein’s main argument: racial segregation was neither an “historical accident” nor the “choice” of non-White groups, but a concerted government objective.

Many Baby Boomers and older Americans today have their own memories of restrictive “racial covenants” attached to their home deeds. Even younger buyers have been shocked to see restrictive racial covenants still attached – though non-enforceable – to their home purchasing paperwork.

“The demographic makeup of our region is very different today in comparison to the period we're analyzing, in part because of major inroads made by civil rights and immigration policies after World War II,” Dr. Krystyn Moon, an historian from the University of Mary Washington and one of the lead researchers on the "Documenting Exclusion & Resilience" project told Arl.Now.Com. “That being said, the residue of the practice of using racially restrictive covenants remains with us today, and inequities persist.”

In “Housing Segregation: Nowhere to Live,” from Deeply Rooted of Historyfortomorrow.org, Falls Church is noted as one of the first cities in Virginia to enact restrictive racial covenants. “In 1912, Virginia authorized “segregation districts,” making it legal for local governments to segregate neighborhoods, an action taken by the city of Falls Church in 1915. When the U.S. Supreme Court banned such ordinances in 1917, white communities in Arlington County and Fairfax County [nevertheless] enacted restrictive covenants that prohibited sales to “non-Caucasian” buyers,” Deeply Rooted reported. “These racially restrictive covenants, as well as exclusionary zoning, urban renewal, and discriminatory loan policies have all been used to restrict and attempt to push out Northern Virginia’s Black population.”

Even in the wake of the 1968 Fair Housing Act banning racially restrictive covenants, many such restrictions “stayed on the books,” Deeply Rooted reported. Not until 2020, did the Virginia General Assembly pass House Bill 788 prohibiting “a deed containing a restrictive covenant from being recorded and provid[ing] the language for a Certificate of Release of Certain Prohibited Covenants to be recorded to remove any such restrictive covenant.”

The Red-Shaded Neighborhoods in The City of Falls Church

A visit to the “Documenting Exclusion & Resilience” website reveals easy-to-use interactive maps, allowing users to examine specific streets on a block-by-block basis, with pop-up features for restrictive racial covenants from historical deeds.

Zooming in on The City of Falls Church, one can see that the majority of racially-covented neighborhoods are on the western edge of the city, though northern neighborhoods around Spruce, Sycamore, Walnut, Pine, North Oak, Highland Avenue and North West Street are shaded red.

Downtown is also pretty red-shaded. East of Cherry Hill Park, within West Broad Street, the W&OD Trail, North Oak Street, Great Falls Street, Northern Virginia Avenue, and Park Avenue, is another discriminatory cluster.

On the east side of the city, red-shading is prevalent west of Fort Taylor Park, between North Roosevelt Street, Midvale Street, East Columbia Street, 16th Street North, and East Broad Street.

On the Southern boundary of the city, every block south of Hillwood Avenue, from Liberty Avenue to the west to South Street in the east is also mostly red-shaded.

Fortunately, much of the center of the city, from Winter Hill to the corner of Route 29 and West Broad Street and from the northern and southern boundaries of the city were without restrictive covenants.

What does your block look like?

**

We applaud the “Documenting Exclusion & Resilience” project and hope further research and mapping can continue to shed light on the “shady” areas of our racial history.

Check out these helpful radio stories about racial covenants and redlining in Virginia:

NPR: Mapping Projects Show Lasting Impact Of Redlining, Racial Covenants In Virginia

NPR: Race & Redlining: Housing Segregation in Everything

By Christopher Jones

Member discussion